Carroll, Robyn; Wallace, Helen --- "An Integrated Approach to Information Literacy in Legal Education" [2002] LegEdRev 8; (2002) 13(2) Legal Education Review 133

An Integrated Approach to Information Literacy in

Legal Education

ROBYN CARROLL* & HELEN

WALLACE **

PART A – INFORMATION LITERACY AND LEGAL EDUCATION

One of the many essential skills of a lawyer is the ability to research the

law. It has been recognised for some time that the skills

required to research

the law should be taught at law school.1 Greater

emphasis in higher education on the importance of teaching generic skills has

coincided with discussion of the need for skills

education for lawyers

generally.2 The increasing interest of universities in

the development of the “life long learner” has focused attention on

methods

of training students to be independent

learners.3

Debate about the appropriateness of legal

research skills training in the law degree has been part of the academic and

professional

library literature for decades but particularly during the

1980s.4 A survey of legal research courses in Australia

in 1991 revealed that most law schools were offering research skills as a

subject

or part of a subject:

Overall, two faculties had no formal course, and two of the new faculties did

not yet have settled curriculum. Of the remaining 17

law schools, nine were

reported as having separate research subjects, seven said research training was

a component of another subject

and one was reported as being part of a skills

workshop. Where research was taught as part of another course it was invariably

a

segment of the first year subject Introduction to Law or its

equivalent.5

The classes generally followed the

format of traditional bibliographic instruction which Murdock described as

“short range,

library centered, print-bound

instruction”,6 with electronic resources being

gradually introduced.

A comparison of Law graduates who completed their

degrees in 1991 and 1995 showed that although overall use of legal research

skills

did not increase, the frequency of use did.7

Table 1: Frequency of Use of Legal Research Skills

by Law

Graduates8

|

|

Used frequently |

Used sometimes |

% of graduates

who use legal research skills |

|

1991

|

50%

|

34%

|

84%

|

|

1995

|

54%

|

29%

|

84%

|

During the 1990s the term “information literacy” entered

education discourse and was taken up by educational institutions

at all levels.

One of the earliest exponents of information literacy in Australia is Christine

Bruce, who has defined information

literacy as “the ability to locate,

evaluate, manage and use information from a range of sources for problem

solving, decision

making and research”.9

Information literacy is critical to lifelong, independent learning in an era of

rapid expansion of information technology. During

the last decade the concept of

information literacy has become embedded in library programs across all

disciplines because of the

emphasis on the need for graduates to be skilled in

the use of information resources.

At the same time, by the mid 1990s the

teaching methodology in law had changed noticeably from bibliographic

instruction to skills

training and recognition of the “process of

research”.10 This change was driven by the rapid

development of information technology: hardware and software products were

constantly being upgraded

and new electronic information resources were keeping

pace. It was no longer possible to “instruct” law students in the

use of a particular product and expect it to be available in the same format

after they had graduated. Students needed the skills

to adapt to new electronic

information products. They also needed the ability to transfer these skills from

one application to another,

across subject boundaries, and from their student

environment to their career environment. The information literacy discourse has

formed, not surprisingly, the basis for reassessment of legal research programs

in Australian law schools.11 The issues facing law

schools have arisen from two directions. On the one hand the demand on

universities to produce graduates with

the generic skills to enter a profession,

and on the other, the demand from the legal profession for the skills to keep

pace with

the burgeoning development of electronic legal information

resources.12

Defining “skills” is no

easy task and we will not attempt that here.13 We are

using the term broadly to equate with information literacy. The QUT

classification of graduate attributes14 is helpful to

our understanding of the place of information literacy in legal education. These

graduate attributes have been described

as discipline knowledge, ethical

attitude, communication, problem solving and reasoning, information literacy and

interpersonal focus.15

Applying Bruce’s

definition of information literacy to the study and practice of Law, it is the

ability to:

- locate legal materials (primary and secondary] using appropriate retrieval tools and techniques;

- evaluate the relevance, applicability, and value of the located materials to the task at hand. This will include assessing the relevance, precedent value and other factors affecting the authority of the material;

- manage the information, that is, to sort, categorise and rank the information; and

- use the information for the task at hand, such as advising on the law, formulating a policy argument or identifying theoretical perspectives presented in the materials.

Information literacy is as much an attribute of the

process of “lawyering” as are discipline knowledge and the ability

to problem solve and engage in legal reasoning. Not surprisingly it will be

difficult at times to draw a line between the information

skills16 involved in locating and knowing how to use

the law (information literacy) and the mental

skills17 involved in applying the law

(discipline knowledge, problem solving and reasoning). In each case there is an

element of problem solving.18 In practical terms, when

we aim to train the “whole lawyer” we would expect there to be a

high level of interface between

these different attributes. Typically, the

specialised nature of legal research tools has meant that reference librarians

have become

involved in the legal research aspect of legal education. The more

we focus on the interface between the various graduate attributes,

the more

obvious becomes the need for close cooperation between law and library

“teachers”.

In 1994 a study commissioned by the National Board of

Employment, Education and Training noted the benefits derived from librarians

working closely with academic staff to develop information retrieval skills in

students.19 This Report refers to a number of

submissions that explore the role of the library in developing lifelong learning

skills. More generally

with respect to legal education, Christensen and Kift

have argued that we will produce better law graduates if we adopt programs

that

integrate both conceptual knowledge and transferable generic and legal

skills.20

A number of programs have been developed

in Australian Law Schools that aim to improve information literacy of law

students through

integration of legal research skills teaching into the law

curriculum. One example21 has been Monash

University’s integration of Legal Research and Methods (LRM) into

alternate years of the undergraduate curriculum.22 At

Queensland University of Technology a range of generic skills have been

integrated into the curriculum. Legal Research and Writing

is a discrete first

year unit rather than being placed in the context of the areas of law being

studied.23 At Flinders University a range of generic

skills have also been incorporated into the curriculum. The foundations of legal

research

skills are taught in a compulsory first year unit, Legal Method. These

skills are then reinforced at each level of the degree by

identifying their

application in conjunction with other skills such as interviewing and

mooting.24 In 1994 Bott reported on the Bond University

program in which library research skills are taught as part of the

“Introduction

to Law” unit, with the Law Library staff playing a

direct role in the planning and delivery of the library skills

program.25

In Part B of this paper we describe a

program recently introduced jointly by the Library and Law School at The

University of Western

Australia. In designing our program, we have drawn on the

literature to identify the ideals‚ on which an integrated legal research

skills program should be based. We have also identified the ideals evident in

other law school programs and those that we set out

to achieve in our own. These

ideals include, that:

- programs should be designed so that graduates will be able to use current technologies and effective strategies for the retrieval, evaluation and creative use of relevant information as a lifelong learners;26

- an integrated legal research skills teaching program will draw on the knowledge of law held by the academic staff of the Law School and the knowledge of information resources and research skills held by librarians;

- legal research is recognised as an integral part of the process of solving legal problems;

- information literacy is relational27 to the discipline in which it exists and therefore legal research skills are best placed in the context of the areas of law being studied;

- as student learning largely is driven by assessment, the acquisition of research skills need to be assessed in some way; and

- research skills will be improved if they are developed, and reinforced, from a level of basic competency level in first year through to advanced skills at the point of graduation.

Other writers have commented on the difficulties commonly encountered in teaching skills in the law curriculum.28 Wade identifies the following frustrations and challenges to teachers attempting to incorporate skills into law units:29

- the shortage of time available for students to undertake practical exercises;

- the lack of a systematic curriculum structure that provides for revision and reinforcement of skills acquired in one unit in subsequent units;

- the lack of commitment within and without the law school to skills teaching;

- insufficient resources to teach skills effectively, for example by the presence of experienced instructors to model skills and provide instant feedback;

- the superficiality of the experience of the majority of students in skills exercises (which he suggests may relate to lack of time and overcrowding in the curriculum30);

- students may not be motivated to learn unless they have opportunity to apply their skills to “real life” experiences, which is difficult to achieve in the absence of “real” clients;

- the form of snobbery that labels teachers who articulate goals of acquisition of skills and also incorporate adult education methods into the learning environment as engaged in “mere” training (original emphasis);

- the labour intensive nature of skills training;

- the teaching burnout that often results from the complex nature of teaching skills;

- the structural and institutional disincentives to choosing skills teaching as a career path;

- the frequent foundering of pilot programs due to lack of institutional foundations of resources, personnel, cultural acceptance and incentives once the dynamism of the program founder is gone;

- the interference of skills teaching with coverage of substantive topics;

- the lack of credibility of law academics to teach practical skills;

- the vagueness of the assessment criteria in assessment methods commonly used; and

- the lack of adequate teaching materials.

Wade’s list is comprehensive, and paints a daunting picture for law schools seeking to incorporate skills training in their curriculum. In addition, a number of other challenges can be identified that have particular application to an integrated approach to teaching legal research skills. These include:

- As researching electronic legal information resources requires a level of information technology skills, disparities in student access to computers and their ability to use the technology has posed difficulties for library teachers. Library staff have observed, however, a significant increase in “starter skills” of students in recent years;

- As students begin their studies with different levels of research skills and experiences, there are inevitable difficulties in pitching the teaching at a level that engages all the students in the group;

- Avoiding overlap or gaps in the training in various law units;

- Measuring and evaluating improvements in student learning outcomes;

- Balancing the amount of online and face-to-face instruction;

- Supporting a culture shift from reference librarians being seen as bibliographic experts to being seen as process educators;

- Resourcing programs that increase the contact time for library staff teaching students;

- Identifying the specific aspects of information literacy that are essential to law students and which aspects need to be addressed in the law school curriculum;

- Facilitating and sustaining cooperation with numerous members of faculty;

- Creating enough room in the teaching program for more research activities; and

- Identifying assessable outcomes and the means to assess them.

In what follows we describe the program offered at UWA prior to 2000, the reasons for change, and the steps taken to create an integrated legal research skills program from 2000 in which we have endeavoured to capture the ideals set out above. In Part C of this article we review our experiences and the many challenges to integrating the teaching of legal research skills into the curriculum.

PART B – INTEGRATING LEGAL RESEARCH SKILLS INTO THE UWA BACHELOR OF LAWS COURSES

Background to the Research Skills Integration Program

Until 2000, our Law students received six hours of instruction in legal

research methods by library staff during the first year of

their course in the

unit Legal Process. Library classes were given on Citation, Case law,

Legislation and Secondary Sources. Attendance at these classes was compulsory

and five percent of the assessment for Legal Process was allocated to a

research journal prepared and presented by students with the major written paper

they submitted for the unit.

Prior to 2000 this was the only compulsory legal

research skills instruction that students received during their law studies.

Academic

staff teaching in some compulsory and elective units increasingly were

making arrangements for the reference librarians to provide

instruction to

students in their units to assist student with research papers for

assessment.

Many of the students in a Bachelor of Laws degree are enrolled in

five-year combined degrees. This has a number of implications. First,

the level

of instruction they are able to absorb in first year is unlikely to equip them

for the more demanding research expectations

placed on them in later years of

the degree. This is possibly the most significant reason to spread research

skills instruction across

the degree. At UWA, approximately three quarters of

the students entering into the degree are school leavers or non-graduates.

Students

study only two law units in their first year at university, the balance

of their studies being in the other faculty in which they

are enrolled.

Consequently, students take two years to complete the four “first

year” law units. There is then a further

year in which second year units

are taken in which limited demands are made for independent library research.

Second, there are limited opportunities for students to use all the areas of

competency in the first and second year law units. There

is a limit to the

amount of independent research for assessable work that can be expected of

students during semester. There are

also difficulties setting common research

tasks for large groups of students because of the limited facilities of the

library. Third,

students who select electives where the assessment is largely

examination based rather than based on independent research may evade

anything

other than rudimentary instruction in the first year of the degree. Fourth, the

growth of computer based research resources

has meant that what students learn

about in first year will often need to be updated within a few years.

Indications that there was a wide range in the level of research skills of

UWA LLB graduates, and the fact that some graduates apparently

did not have

essential research skills31 prompted the Law School in

late 1998 to review the ability of the current program to achieve an acceptable

level of competency.32 The library staff reported that

it was impossible to achieve the necessary coverage of even basic research

materials under the existing

arrangement. A meeting of the staff

concluded that greater emphasis should be placed in the curriculum on legal

research skills. To this end, in

May 1999, the Faculty appointed a member of

academic staff as Research Skills Co-ordinator, to work with the library and

academic

staff to develop an expanded legal research skills program.

In

October 1999 the Law School and the University Library were granted funds under

the University of Western Australia Teaching and

Learning Initiatives Scheme to

“develop and implement a collaborative strategy for improving information

literacy through integration

of legal research skills instruction into law units

at all levels of the LLB”. The objectives were to:

- achieve a higher and more consistent level of student legal research skills competency;

- enhance existing and develop further collaborative practices relating to research skills instruction between the Law Faculty and the Library;

- develop instructional material that facilitates integration of legal research skills instruction into law units;

- improve legal

research skills education of law students by:

- - increasing the amount of legal research skills instruction provided to law students

- - reinforcing the legal research skills taught in the first year of the degree

- - increasing the number of opportunities to practice legal research skills over the course of the degree

- - offering legal research instruction in a timely manner and at an appropriate stage of the LLB degree.

A Working Group comprised of the Research Skills Co-ordinator, the Law Librarian, two reference librarians and an Instructional Designer met on a regular basis between October 1999 and March 2000 during the design and planning phase, and have met since then during the implementation and evaluation phases.

Design and Implementation of the Research Skills Integration Program

During the early stages of the project, the Working Group identified five key strategies to achieve the project objectives.

Strategy 1 – To determine the areas and levels of skill competency that students should acquire during the degree and an outcome statement of those skill levels.

The areas of skills competency specific to legal research were identified as Citation, Case law, Legislation and Secondary Sources. The levels of skills competency were identified as Basic, Intermediate and Advanced. A Table of Core Competencies was developed by the library staff in consultation with members of the academic staff. This Table provides an outcome statement that students can use to monitor their level of skills and against which the effectiveness of the research skills program can be evaluated. A copy of the Table (updated for 2001) is included as Appendix A.

Strategy 2 – To identify the year levels and compulsory units in which research skills might be taught.

These units were selected by applying various

criteria, including whether informal arrangements already existed, the

assessment structure

in the unit, and timing within the degree structure. Six

compulsory units were selected, (in addition to Legal Process where library

classes have been held for many years). As a result of integrating legal

research into seven compulsory units, the amount of instruction

each student

receives has increased from six hours to more than twelve hours.

Until 1999,

classes in the compulsory units were aimed only at achieving basic and

intermediate levels of competency. In 1999 an effort

was made by the library

staff to cover all levels of competency in the first year unit Legal

Process. At the same time some ad hoc arrangements were made between

the library staff and some academic staff to provide further research skills

training in two other

first year units, Torts and Criminal

Law.

Table 2 shows the formal arrangements for legal research skills

instruction in 1999. This can be contrasted with the formal arrangements

put in

place in 2000 as a result of the project.

Table 2: Legal Research Skills Integration – 1999

|

|

Legal Process 130

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Advanced

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Case Law

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Legislation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary Sources

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intermediate

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Citation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Case Law

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Legislation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary Sources

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Basic

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Citation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Case Law

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Legislation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary Sources

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3 shows the areas of skills instruction, the skills level and the units in which the teaching program includes legal research skills learning activities from 2000.

Table 3: Legal Research Skills Integration – From 2000

|

|

Legal Process 130

|

Criminal Law

100 |

Torts

120 |

Equity

202 |

Admin Law

320 |

Con Law

2401 |

Procedure

020 |

|

Advanced

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Case Law

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Legislation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary Sources

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intermediate

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Citation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Case Law

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Legislation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary Sources

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Basic

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Citation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Case Law

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Legislation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary Sources

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The effect of the integration program is to postpone instruction at intermediate and advanced levels until later years of the degree. The benefit of this arrangement is that there can be greater certainty that students will have acquired and retain advanced research skills at the time they graduate.

Strategy 3 – To explore with co-ordinators of the compulsory units in which legal research skills would be taught the best ways to integrate that instruction into the unit.

To assist that process, a detailed planning

checklist was created.

The reference librarians worked closely with the unit

co-ordinators of the selected compulsory units to generate the instructional

materials used in library classes and research activities. In this way it was

possible for the law staff to provide the library staff

with research tasks that

are relevant to the materials being studied in the unit and that students are

likely to encounter as graduates.

The instruction methods adopted by the library

staff in the various compulsory units ranged from

- a combination of lecture and activities in dedicated library classes with groups of 15 (Legal Process)

- lectures during scheduled class time in regular teaching venues with law staff present (Criminal Law, Equity, Procedure)

- lecture/demonstrations during scheduled tutorial times in the Law Library electronic training room (Administrative law)

- self paced exercises carried out in student’s own time (with assistance from library staff as and when needed) (Torts, Constitutional Law 2).

The specific integration methods adopted in 2000 were as follows:

Legal Process

Classes on using the library and specific research

tools for citation, case law, legislation and secondary sources were conducted

by the library staff (as in previous years). The classes aimed at giving

students a basic level of competence in these areas. Attendance

was compulsory

and students were required to complete a written exercise for each of the four

classes. Failure to successfully complete

each of the exercises would result in

a fail grade.33 Students were also required to submit a

research Journal with their second semester Legal Process assignment,

explaining the process undertaken when researching a nominated topic and drawing

on what they had learnt in their library

classes. Ten per cent of the marks for

Legal Process were assigned to the Journal.

Criminal Law

Criminal Law classes consist of about 35 students.

Library staff conducted a class for each group during the usual class time in

first

semester, just after students received their first Criminal Law

assignment. The classes aimed to assist students to prepare their research

assignment, due early in second semester. The materials

presented were developed

in consultation with the Criminal Law lecturers and focused on

researching Criminal Law sources.

Torts

Students were given a self-paced exercise during first

semester. The Torts lecturers provided the library staff with the

information they wanted the students to locate. The librarians devised a series

of

questions that required students to use sources specified by the Torts

lecturers. The aim of the exercises was to provide students with practice using

particular research tools before they commenced work

on their research

assignments. The material discovered during these exercises was part of the

reading required for discussion in

the following seminar class. Students might

be asked to locate, for example, a recent unreported case, or the transcript of

an application

for special leave to appeal to the High Court.

In second

semester students were required to submit a research journal as part of their

research assignment, worth five per cent of

the assessment for the unit. The

journal required students to demonstrate that they had reflected on the process

of research. Students

were expected to document how they developed and executed

their research strategy.

Equity

Two lectures were given to the class by the reference

librarians during the scheduled class time in week ten of first semester.

Although

the lecture primarily focused on secondary sources relevant to the

areas that students might be expected to research, some coverage

of case law and

legislation research was included at the unit co-ordinator’s request.

Students were given prepared handouts.

Attendance at class was

compulsory.34

The coverage in the lectures was

linked to the 100 per cent examination at the end of semester. Prior to the

library class, students

were given a handout that detailed the areas that would

be the subject of essay questions in the examination. Students were told

that

they must answer one essay question in the examination, that the questions would

be based on the published essay areas and that

marks would be given for

demonstrated understanding of an area through materials other than those

published on the unit reading list.

Students in the unit were also provided with

a one hour tutorial on what was expected of them in an essay question in an

examination.

Administrative Law

Classes were held during the scheduled tutorial

time at the beginning of semester two for groups of 15 students in the library

electronic

training room. The topic researched by the class was delegated

legislation. The administrative law principles concerning delegated

legislation

had been covered and assessed in first semester. Attendance was voluntary and

about 60 per cent of the class attended.

Constitutional Law 2

Students were encouraged to complete a

worksheet in their own time in this second semester unit. The exercise was not

compulsory and

there was no formal contact with the library staff. There is no

record of how many students completed the exercise, although a questionnaire

circulated at the end of semester would suggest that it was not a high

proportion. The content of the questions in the worksheet

focused on researching

legislation that was central to the case discussed in the first tutorial. The

questions were compiled by the

unit co-ordinator and the library staff added

instructions to the worksheet on how to use electronic sources to answer the

questions.

The worksheet was not directly linked to the assessment in the unit.

Procedure

The library staff gave a 30 minute lecture to students

following the scheduled class during week two of first semester. The content

of

the lecture was based on an interview with a recent graduate who had

considerable experience with library work. The unit co-ordinator

attended the

class and interspersed the lecture with comments about the ways students would

use the various research tools in their

work in the unit.

Strategy 4 – Generation of teaching materials for each law unit

To prepare teaching materials for each new class by the library staff. The library staff consulted the Instructional Designer for the Faculties of Economics, Commerce, Education and Law for advice on the design of these written teaching materials. The planning also took into account how WebCT could be used in this area of teaching. A considerable amount of time was spent preparing the teaching materials necessary to extend the research skills classes into the additional law units. These materials provide a record for students of the legal research tools and problem solving methods used during class and other research activities. Towards the end of 2000 the library staff developed and piloted the use of WebCT to teach Citation. Further use has been made of this software in 2001.

Strategy 5 – Creation of a Student Manual

To create a Student Manual. This strategy evolved as the planning progressed. It became clear that we needed some way for students to understand the ongoing nature of the integrated legal research skills program. The Working Group identified a number of objectives in creating the Student Manual. These included:

- raising the profile and reinforcing to students the importance of legal research as a key aspect of legal education and legal practice;

- providing students with a physical resource in which they could organize and retain relevant legal research skills documents;

- encouraging students to collect useful material over the duration of their degree;

- assisting students to take responsibility for their own information literacy;

- increasing student awareness of legal research skills as a life-long skill.

The Manual consisted of an A4 two-ring binder and was distributed to all first year students at the beginning of first semester 2000. The purpose of the Manual and the importance of legal research skills were explained to students at that stage. The Manual contained an introduction and overview of the integrated program of research skills instruction they would receive during their degree. A copy of a chapter on legal research from a leading text35 in the area was included. The teaching material for the first library class in Legal Process was also included.

Evaluation of the Program

As the integration program will take effect over five years it will be difficult to evaluate its overall effectiveness until the students who entered the Law School in 2000 graduate, in 2003–2005. With this in mind, the Working Group identified two levels of evaluation to form the basis of evaluation of the project in 2000 and on an ongoing basis.

Overall effectiveness of the program

The Working Group decided during the planning stage to find a way to measure whether this objective had been achieved. As the integration program will not be fully implemented until 2004, it was decided to devise a means of collecting data that measures the learning outcomes during the five years it will take to be fully operational. Consequently a 20 question “test” was devised by the reference librarians and administered to the students in Legal Process, Torts, Equity and Procedure in March 2000. A preliminary reading of these results indicates that, on average, second to fourth year students have a basic to intermediate level of competency in legal research skills. The “test” was administered again at the beginning of 2001 to students in the same units. This process will be repeated until 2004. We hope to observe an overall improvement in the average level of competency in later year units. (We would not expect any change to the result in Legal Process.)

Review of instructional material, teaching activities and student manuals

The evaluation at this level has taken into account the perceptions and comments of the three key groups involved in the integration program, namely students, library staff and academic staff. These perceptions and comments have been collected via:

- oral and written feedback from academic staff;

- biannual written reports prepared by the library staff for the Library;

- written student evaluation of library classes in Legal Process

- written student evaluation of the Student Manual;

- A questionnaire administered to students in Constitutional Law II;

- informal oral feedback from students; and

- a half day review and planning meeting conducted by the Working Group.

Evaluation by students

Student Manual.

Student evaluation of the Legal Research Manual was very positive. Students

completed a feedback sheet placed in the back of each

Manual (Appendix

B). A total of 188 responses were received. (Approximately 80 per cent of

students commented on Question 1. There was a dramatic decrease

to about 30 per

cent for Questions 2 to 5.) A summary of the results for Question 1 of the

survey are outlined in Table 5 and presented

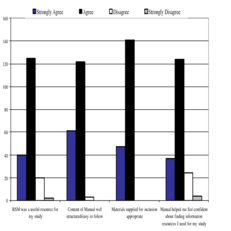

in graph form in Table 6.

Table 5: Evaluation of Student Legal Research Skills Manual – 2000

|

Question

|

Strongly

Agree |

Agree

|

Disagree

|

Strongly Disagree

|

|

Manual was a useful resource for my study

|

40

|

126

|

20

|

2

|

|

Content of Manual well structured/easy to follow

|

61

|

122

|

5

|

0

|

|

Materials supplied for inclusion appropriate

|

47

|

141

|

0

|

0

|

|

Manual helped me feel confident about finding information resources I need

for my study

|

36

|

125

|

23

|

4

|

Table 6: Legal Research Skills Student Manual Feedback

Written responses to Questions 2, 3, 4 and 5 provided useful

feedback to the librarians about the materials contained in the Manual,

and the

length and timing of the library classes in Legal Process. A majority of

respondents found the Manual to contain relevant and useful information and

stated that they had no difficulty using

it. A common suggestion for improvement

was to reduce the physical size of the folder that contains the Manual. It was

also suggested

that students should have more “hands on” exercises

to reinforce learning.

Unit activities. The librarians arranged for a

Student Perception of Teaching (SPOT) survey of the library classes held in

Legal Process. Comparison of the 1999 and 2000 SPOT results demonstrates

a favourable increase in the students’ perception on a range of

matters.

This improvement is attributed by the librarians to changes made between 1999

and 2000 as a result of the integration project.

Table 7 provides a comparison

of 1999 and 2000 SPOT results.

Table 7: Comparison of SPOT Survey Results – 1999 to 2000

|

Question |

1999

mean |

2000

mean |

difference |

|

I have improved my research skills in this field

|

4.01

|

4.06

|

0.05

|

|

The teacher seems to have been well informed on the material

presented

|

4.48

|

4.43

|

-0.05

|

|

The teacher has been approachable

|

4.29

|

4.41

|

0.12

|

|

Material has been delivered at the right pace

|

3.65

|

3.75

|

0.10

|

|

Sufficient time has been given to complete work in class

|

3.50

|

4.09

|

0.59

|

|

Good use has been made of examples and illustrations

|

3.99

|

4.08

|

0.09

|

|

There has been a good balance between theory and application

|

3.83

|

4.01

|

0.18

|

|

The amount of material covered has been reasonable

|

3.64

|

4.04

|

0.40

|

|

These classes have been a valuable part of this unit

|

3.89

|

3.97

|

0.08

|

|

Handouts and notes have helped me understand the material

|

3.99

|

4.39

|

0.40

|

A review of the written comments on the SPOT survey by the librarians

established that the comments were generally positive, with

most students

writing that they believed the classes were worthwhile and the exercises

effective. Other comments included that the

librarians conducting the classes

were friendly, the handouts useful, the classes well organised and the coverage

good.

A questionnaire was administered to students in Constitutional Law

II evaluating the exercise set in that unit. The number of completed forms

was low, although this can be attributed to the fact that

the exercise was not

compulsory and the questionnaire was not administered until the end of semester.

(The exercise took place early

in the semester.) The comments received have been

useful though in reviewing the exercise in 2001. Of the 207 students enrolled in

the unit there were 64 returns. Of these, 37 students answered yes to the

question whether they had completed the exercise. The general

tenor of the

comments from these students was that they found the exercise very useful

because of what they learnt about researching

legislation. Other comments

included requests to make the instructions to follow easier to understand and

that some credit be given

for completing the exercise or at least some feedback

on the exercise in class.

A number of students who attended the

Procedure class commented that the presentation and written handouts were

very useful. Some of the students reported that they were concerned

about how

difficult they found it to answer the questions in the “test” that

was administered at the beginning of the

class, and that this encouraged them to

pay attention during the class. This suggests that the “test” may

serve a dual

purpose: as an evaluation tool and as a teaching device.

Evaluation by Library Staff

Student Manuals. The librarians

found it helpful to be able to refer to the reference material in the Manual. It

was observed that the students had

some difficulty with the size of the folder

and staff noted to use a slimmer folder in 2001 (which has been

done).

Unit Activities. The library staff perceived their teaching in

Legal Process in 2000 to have been far more effective than in previous

years because they were not trying to cover as much in that unit as they

had

before. They no longer attempted to teach advanced level skills, as they had in

1999, knowing that instruction at this level

will take place later in the degree

course.

Evaluation by Academic Staff

Student Manual. Although no

general survey of responses to the use of a Student Manual by members of the

academic staff has been undertaken, favourable

comments have been received by

the Research Skills Co-ordinator from a number of staff members. Members of the

academic staff involved

in teaching first year units and the Law School Teaching

and Learning Committee decided in February 2001 to expand the Student Manual

to

include materials on Legal Writing. This is an endorsement of the concept of a

Manual that straddles the compulsory units of the

degree.

Unit Activities.

There is strong support by the academic staff teaching the compulsory units

in the integration program for the teaching activities

that have been developed

and the involvement of the reference librarians. Each of the unit co-ordinators

involved in the integration

program in 2000 has agreed to continue with the

arrangements made last year. In some cases, for example Equity, there was

extensive consultation in 2001 between the library staff and the unit

co-ordinator to reduce the administrative burden

associated with the initiative

in that unit and, at the same time, to improve the learning outcomes for the

students.

The Legal Process unit co-ordinator in 2000 commented

favourably on the standard of the research journals completed by Legal

Process students as part of their second semester assignment. The

Equity unit co-ordinator reported that the quality of essays in the

Equity end of semester examination far exceeded that in the previous

year, there being clear evidence of independent research and analysis

of the

materials researched. She also commented that, disappointingly, the research did

not seem to translate into a better quality

of problem answer in the

examination. The unit co-ordinator reported that the feedback obtained from the

students in that unit on

the library lectures was, by and large, very positive.

She also reported that some comments were made about the level of sophistication

of the first lecture given by the librarians, and suggestions made by students

for possible ways to accommodate these comments.

The Criminal Law unit

co-ordinator reported that students found the classes very useful for the

preparation of their 2000 first semester assignment.

The unit co-ordinator also

reported a higher incidence of plagiarism in these assignments and suggested

that greater efforts need

to be made to instruct students how to use and cite

the sources they research.

The Administrative Law and

Procedure unit co-ordinators have reported that the classes in their

units were timely and well presented to students. They each reported the

materials presented to students to be at an appropriate level and relevant to

the unit.

Arguably, the activity in Constitutional Law II was the most

closely linked to a class activity and was the most difficult to structure. The

aim of the unit co-ordinator was to combine

learning and application of the

search process with learning about and understanding the constitutional law

issue. Consideration

is still being given how to achieve this level of

integration in a way that is workable, taking into account the student’s

desire for “reward for effort” if they complete the exercise, the

small number of staff involved in teaching the unit,

and the limited teaching

time to cover the substantive topics.

New Developments and Future Directions

During the planning and implementation stages in 2000 a number of possibilities presented that would supplement or augment the program. These are described briefly below.

Use of WebCT

The most significant development in 2001 is the use of WebCT, a software program that enables students to complete self paced exercises online. These exercises can be repeated by a student as often as they wish until they submit their work for automatic assessment by the program. This will save the library staff manually marking the students tests as in previous years. The mark that is recorded is available to staff in a report in a spreadsheet generated automatically by the program. WebCT will be used this year in Legal Process and Equity. In Equity, compulsory completion of a WebCT exercise has replaced compulsory attendance at the library skills lectures. The staff involved in using this program for the unit Equity believe that is a good step, but there have been many time consuming “bugs” in the system.

Online publication of the Student Manual

The Working Party proposes to make the material in the Manual and library teaching materials available online later this year.

Legal Writing Skills materials included in the 2001 Student Manual

In 2001 a new section was inserted in the Student Manual on Legal Writing. This section was prepared in consultation with the co-ordinator of Legal Process, and other first year unit co-ordinators. Only a small amount of material on legal writing was included this year, but it is hoped that greater use will be made of this part of the Manual, now called the Legal Research and Writing Skills Manual, in future years.

PART C – COMMENTS AND CONCLUSIONS

Key Features of the UWA Program

The key features of the program we have introduced at UWA are:

- Legal research skills instruction is integrated into seven compulsory units at all year levels throughout the degree.

There is no dedicated legal research unit in the degree, but classes and exercises are integrated into the units. This enables us to refresh and reinforce the skills taught in earlier years and to emphasise the transferable nature of the skills.

- The legal research skills instruction is provided by library staff in close collaboration with the academic staff responsible for the compulsory units.

The Library has deliberately been pursuing a policy of involving reference librarians in training rather than providing ad hoc assistance to students. This policy is consistent with a view that legal research is a process rather than a static knowledge base. The ultimate goal therefore, is for students to become independent researchers. The Student Manual is a key strategy to achieving this goal, with students being expected to refer to their previous training information to answer their research inquiries. Despite the primary emphasis on training, the reference staff remain available to assist students with research inquiries.

Perhaps the most significant feature of the program is that it aims to address the fourth element of information literacy, namely the “use of information” which in law includes writing skills – “the lawyer’s ultimate goal – the closure, the end of the research process?”36 Hutchinson and Fong have pointed out that a narrow view of legal research predominates in the literature.37 Arguably, the broader perspective of information literacy will break through this restrictive view.

One of the most rewarding aspects of the program for all staff involved has been the opportunity for collaboration between library and academic staff. The library staff have appreciated the support provided by the academic staff, and believe it has had a significant impact on student attitudes about the importance of research skills to their legal education.

- The Student Manual is a resource that reinforces the integral nature of the skills training and the incremental nature of learning.

The Student Manual was an innovation for the UWA Law School in that it is not directly associated with any particular unit in the degree. The Manual is progressively compiled following instruction by both academic and library staff, and through a combination of lecture, demonstration and practical classes over the course of the degree. The potential value of the Manual as a resource while at Law School and in the workforce is explained to students at the beginning of their studies.

Difficulties and Challenges

Many of the difficulties outlined in Part A have been encountered at some stage and some of them continue to pose difficulties for the program. In our view, the most significant challenges we face are:

- Lack of resources to fund the program

Additional teaching means additional salary costs. Whether the salary is funded by the Law School or the Library, competing demands for scarce funds means that there is constant pressure to reduce staff costs.

- Impact on other roles and initiatives by the Library

Clearly there are implications for the library staff from the integration program. The nature of their role has changed from regularly advising on a one off basis to a training role. There are other implications too. Concentration of training in the compulsory units has reduced the availability of library staff to run research sessions in elective units. A number of academics had arranged in previous years for special classes to assist students with their research projects in areas like Comparative Law and Public International Law. It is a considerable challenge for the library staff to cover these areas within the compulsory units (even with the expanded training program) sufficiently to meet the research needs in specialized areas of law. As ever, the critical resources of staff and time mean that limits are imposed on what is covered (as in all areas of the curriculum). An important part of the evaluation of the program over time will be to determine whether the research skills acquired by students in the compulsory units is sufficient for the research tasks students encounter in their elective units.

- Availability of key personnel

The nature of the program is that it requires a considerable amount of coordination. There has been a minimum of eight academics involved in the program and two reference librarians. While these staff members are committed to the program, not all of them will be involved in teaching every year and heavily stylised activities may not suit the staff who replace them. Essentially, maintaining the impetus and enthusiasm for a program so that it outlives the people who put it together is a major challenge. We have sought to address this issue mainly by creating materials in the early stages of the program that make it easier for new staff to continue along similar lines.

Conclusions

The demand on universities to produce graduates with generic research skills applicable to print and electronic resources, and the demand from the legal profession for graduates with the skills to be able to keep pace with new electronic information resources, has in combination prompted many law schools to review their legal research teaching methods and programs. Influenced by this demand for information literate graduates, equipped as life long learners, there has been a discernible shift of emphasis in library classes from the traditional bibliographic instruction method to skills training and recognition of research as a process. At the same time, there has been a movement in many law schools to integrate skills training into the curriculum. In this paper we have presented a program recently developed at The University of Western Australia that aims to produce information literate law graduates through a program of research skills training that is integrated into all years of the curriculum and is taught collaboratively by library and academic staff. Early evaluation indicates that there will be positive outcomes from this program, but that there are many challenges to be met.

Appendix A: Legal Research Skills 2001

|

|

Resources

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

BASIC

|

Citation

What do the abbreviations mean?

Is the citation for a reported or unreported case? When is it appropriate to use square or round brackets? Is the citation for an electronic or print version of the case?

only party names are

given

the given citation is incorrect or incomplete an alternative citation is needed |

|

|

|

Case Law

|

|

|

|

Legislation

Bills;

Explanatory Memoranda; Hansard; Acts; Delegated Legislation.

Act Name;

Act Number; Assent Date; Short Title, Commencement; Interpretation; Main Body;

Tables.

By Act Name

By Act Number By Subject |

|

|

|

Secondary Sources

Identifying keywords and phrases

Searching electronic media

Legal Encyclopaedia; Text Books; Dictionaries

Author; Title; Keyword;

|

|

|

INTER-MEDIATE

|

Case Law

Students will be able to

locate State or Commonwealth case law on a specific section of an Act using the

Australian Digest or Australian

Current Law Reporter

Determining main keywords and

phrases

Using Indexes effectively Searching electronic media

|

|

|

|

Legislation

Commencement information

Date of Assent Date of Proclamation

Latest Reprint

Amendments

Weekly Digest of Bills (WA) - WWW

Bills Tables (Cwth) - print and WWW

Parliamentary

Debates - WA and Commonwealth

WWW Hansard sites - WA and Commonwealth |

|

|

|

Secondary Sources

Search Engines

Online Indexes

Currency; Accuracy; Original

Content; Informative or Promotional; Hosting site; Academic or Commercial

Internet

document

CD-Rom

Subject Searching

|

|

|

AD-VANCED

|

Case Law

|

|

|

|

Legislation

By Name

By Subject

Commencement

|

|

|

|

Secondary Sources

Loose-leaf services; Reports; Conference &

Other Papers; Reference Materials.

Material from other jurisdictions

Court Forms & Precedents

Other Forms & Precedents |

|

Appendix B

Legal Research Skills Student Manual

Feedback Form

We wish to make this Research Skills Manual as helpful as possible for future students, so we would appreciate your feedback about your experience with it. At the end of your library classes on Legislation you will be asked by the Law Librarians to complete this Feedback Form. Please take the time to complete the Form at that time and return it to them. Any informal feedback in the meantime would be appreciated and can be given to the Law Librarians.

|

SA = strongly agree A =

agree D = disagree

SD = strongly disagree Please place a in the appropriate column

|

|

|

|

SA

|

A

|

D

|

SD

|

|

1

|

The Research Skills Manual was a useful resource for my study.

|

|

|

|

|

|

2

|

The content of the Manual was well structured and easy to follow.

|

|

|

|

|

|

3

|

The materials supplied for inclusion in the Manual were appropriate.

|

|

|

|

|

|

4

|

Having the Manual has helped me feel confident about finding the

information resources I need for my study.

|

|

|

|

|

What part of the Manual do you feel was of most value for your own

study/research this semester?

What part of the Manual was of least value for your own study/research

this semester?

Comment on any difficulties you found in using the Manual.

What suggestions would you make for improving the Manual?

Any other comments?

Thank you for your time.

* Senior Lecturer, Law School, The University of Western Australia.

** Law Librarian, The University of Western

Australia.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contribution to

the program discussed in this paper by Penny Jones and Sheelagh

Johnson, UWA

Library; Deborah Ingram and Eileen Thompson, Instructional Designers in the

Faculties of Economics, Commerce, Education

and Law; and various members of the

academic staff, UWA Law School.

©2003. (2002) 13 Legal Educ Rev

133.

1 D Pearce, E Campbell & D Harding, Australian Law Schools: A Discipline Assessment for the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission: A Summary (Canberra: AGPS, 1987) 30; C McInnis and S Marginson, Australian Law Schools After the 1987 Pearce Report (Canberra: AGPS, 1994) 25, 168-70, 251; P Kinder, Taught but not Trained: Bridging the Gap in Legal Research, in Cross Currents: Internationalism, National Identity and the Law, 50th Anniversary Conference of the Australasian Law Teachers Association (1995) 2 [referred to as Cross Currents], <www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/alta/alta95/kinder.html>

2 Australian Law Reform Commission, Managing Justice – a Review of the Federal Civil Justice System, ALRC Report No 89, Part 2 (Canberra: AGPS, 1999) <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/alrc/publications/ reports/89> S Christensen & S Kift, Graduate Attributes and Legal Skills: Integration or Disintegration? (2000) 11 Legal Educ Rev 207; Rethink on Legal Education in Scotland, (2000) CLE Newsl (December) 2; Benchmark Standards for a Law Degree in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (2000), CLE Newsl (December) 4. (It is interesting to note that no mention is made of research skills in the accompanying item: New Australian Competency Standards for Entry Level Lawyers (2000) CLE Newsl (December) 3.

3 P Candy, G Crebert & J O’Leary, Developing Lifelong Learners Through Undergraduate Education, NTEB Commissioned Report No. 28 (Canberra, AGPS, 1994) <http://www.detya.gov.au/nbeet/publications/pdf/ 94_21.pdf> R Lee, From the Classroom to the Library and from the Library to the Workstation: Redefining Roles on Legal Education (1999) 30 Law Libr J 40-41.

4 A Morse, Research, Writing and Advocacy in the Law School Curriculum (1982) 75 Law Libr J, 232–64; S Kauffman, Advanced Legal Research Courses: a New Trend in American Legal Education (1986) 6 Legal Reference Services Q (No 3/4) 123–39; C & J Wren, The Teaching of Legal Research (1988) 80 Law Libr J 7–61; R Berring & K Vanden Heuval, Legal Research: Should Students Learn it or Wing it? (1989) 81 Law Libr J 431–449; J Howland & N Lewis, The Effectiveness of Law School Legal Research Training Programs (1990) 40 J legal Educ (No 3) 381–91; C & J Wren, Reviving Legal Research: a Reply to Berring and Vanden Heuval (1990) 82 Law Libr J 463–96.

5 T Hutchinson, Legal Research Courses: the 1991 Survey (1992) ALLG Newsl No 110 (June) 88.

6 J Murdock, Re-engineering Bibliographic Instruction: the Real Task of Information Literacy (1995) Bull Am Soc’y Info Sci (February-March) 26-27.

7 S Vignaendra, Australian Law Graduates’ Career Destinations (Canberra: DEETYA, 1998) 39.

8 Adapted from Vignaendra, Id at 39.

9 C Bruce, Developing Information Literate Graduates: Prompts for Good Practice, in D. Booker ed, The Learning Link: Information Literacy in Practice, (Adelaide: Auslib Press, 1995) 245–52. Also available online:<www.fit.qut.edu.au/InfoSys/bruce/inflit/prompts.html>

10 Kinder, supra note 1, at 3.

11 E Barnett, Legal Research Skills Training in Australasian Law Faculties: A Basic Overview – the Issues, in Cross Currents, supra note 1. Also available online: <www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/alta/alta95/ barnett.html>; H Culshaw & A Leaver, Information Literacy and Lifelong Learning: Case Study – The Legal Profession, paper presented at the LETA 2000 Conference <http://www.leta2000.sa.edu.au/papers/html> .

12 G Gasteen & C O’Sullivan, Working Towards an Information Literate Law Firm, in C Bruce & P Candy eds, Information Literacy Around the World: Advances in Programs and Research (Wagga Wagga: Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University, 2000) at 110-11.

13 For a useful discussion of the meaning of ‘skills’ and the historical ‘waves of skills goals’ of Australian law schools see J Wade, Legal Skills Training: Some Thoughts on the Terminology and Ongoing Challenges (1994) 5 Legal Educ Rev, 173. For further discussion, see S Kift, Lawyering Skills: Finding Their Place in Legal Education [1997] LegEdRev 2; (1997) 8 Legal Educ Rev 43.

14 F Martin, The Integration of Legal Skills into the Curriculum of the Undergraduate Law Degree: The Queensland University of Technology Perspective (1995) 13 J of Prof Legal Educ 45; referred to by Christensen & Kift, supra note 2, at 215.

15 Christenson & Kift, supra note 2, at 216.

16 R Carter, A Taxonomy of Objectives for Professional Education (1985) 10 Stud Higher Educ, at 135; reproduced by Kift, supra note 13, at 48.

17 Id.

18 Flynn argues that one way of identifying the legal research skills that we expect our graduates to possess is to reflect on the nature of the problem solving process. For his discussion of the skills needed to problem solve see M Flynn, Legal Research Skills: What are they? When Should They be Taught? How can they be Taught? And what About the Other 34 Skills that Law Graduates Frequently Use?, paper presented at the Conference of the Australasian Law Teachers’ Association (Canberra: 2000) <http://www.law.ecel.uwa.edu.au/ab358/martin/alta.htm>

19 Candy, Crebert & O’Leary, supra note 3.

20 Christensen & Kift, supra note 2, at 213; C Bruce, The Seven Faces of Information Literacy, (Adelaide: Auslib Press, 1997) 41; Bruce & Candy, supra note 12, at 6-7; D Chalmers & R Fuller, Teaching for Learning at University: Theory and Practice (London: Kogan Page, 1996).

21 The examples given here do not attempt to be a full account of similar programs at other universities. The authors would be interested to learn of initiatives in other law schools.

22 Kinder, supra note 1.

23 Christensen & Kift, supra note 2.

24 Culshaw & Leaver, supra note 11, at 9.

25 B Bott, Law Library Research Skills Instruction for Undergraduates at Bond University: The Development of a Programme [1994] LegEdRev 6; (1994) 5 Legal Educ Rev 118, at 119.

26 Christensen & Kift, supra note 2.

27 Bruce, supra note 19, at 39.

28 See, for example, J Wade, supra note 13.

29 Id. Although Wade refers to frustrations and challenges he identifies as existing for teachers attempting to incorporate ‘third wave’ skills into law units, they are also pertinent to integrating legal research skills into the curriculum.

30 Id at 185.

31 These concerns were, in part, based on anecdotal information provided to the law librarians by law librarians in various law firms. Similar concerns were reflected in a survey conducted by the Monash Law School, see Kinder, supra note 1.

32 For earlier discussion of these concerns see Flynn, supra note 18.

33 Students are given the opportunity to resubmit the written exercises if they fail it the first time around.

34 There were difficulties with compulsory attendance and enforcing the policy took up a lot of the lecturer’s time in 2000. In 2001 she overcame this problem by creating a compulsory online exercise (using WebCT) which drew on the material covered in the lectures. Attendance at the lectures in 2001 was not noticeably reduced.

35 I Nemes & G Coss, Effective Legal Research (Sydney: Butterworths, 1998).

36 T Hutchinson & C Fong, Objectivity and

Omissions?: The Current Batch of Australian Legal Research Texts Reviewed,

Paper presented to the 8th Asia-Pacific Specials, Health & Law Librarians

Conference, Hobart, Tasmania,

24 August (1999),

at

1.

<http://www.alia.org.au/conferences/shllc/1999/papers/fong.html>

37 Id