Sifris, Adiva; McNeil, Elspeth --- "Small Group Learning in Real Property Law" [2002] LegEdRev 10; (2002) 13(2) Legal Education Review 189

TEACHING NOTE

Small Group Learning in Real Property

Law

ADIVA SIFRIS* & ELSPETH

MCNEIL* *

INTRODUCTION

In Techniques for Teaching Law, Hess and Friedland express their enthusiasm for “Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education” as valuable guidelines for legal educators.1

- Encouraging student-staff contact;

- Encouraging cooperation among students;

- Encouraging active learning;

- Giving prompt feedback;

- Emphasising effective time management;

- Communicating high expectations and

- Respecting diverse talents and ways of learning.

As committed legal educators,

the authors of this article are guided by these principles in their teaching

practice and believe that

“while traditional legal education emphasised

the acquisition of knowledge or ‘cognitive learning’, today

professional

legal education must seek to achieve other

goals”.2 If Law graduates are to be equipped with

lifelong skills and attributes then these goals must include the growth of

interpersonal

and communication skills in context throughout the undergraduate

degree.

The learning and teaching of real property law is a challenge for

both student and teacher. In accordance with the requirements of

the Victorian

Council of Legal Education, it is a compulsory subject in the law degree.

Students of Property Law, a core, full year

subject at Monash University, are

generally in the second or third year of their law degree and have completed a

small number of

law subjects.3 It is the first

conceptually difficult subject that students encounter in their undergraduate

degree and, as a result, Property Law

often has the highest annual failure rate

in Monash Law. Anecdotally, students embark on the study of Property Law with a

great deal

of apprehension and trepidation.

Traditionally, Property Law has

been taught by means of lectures, supported by tutorials. Students have also

been encouraged to study

in small groups as described below. Although the

tutorials provide a forum for interaction, discussion and problem-solving in a

medium-sized

group, the enrolments in each lecture stream and the size of the

lecture spaces needed to accommodate them are not conducive to encouraging

students to engage actively with the class and with the subject matter.

Assessment has traditionally been by examination or by examination

and research

assignment.

Against this background and in light of their respective

experiences as teachers of Property Law, the authors sought to improve student

attitudes to and the learning and teaching of Property Law as well as the

profile of the subject. They decided to pilot a small

group4 learning project that would implement principles

of good teaching practice and provide a team based, collaborative learning

environment

in which students of Property Law could gain confidence and learn

among their peers, engage in active learning5 and

extend their interpersonal and communication skills.

In this article the

authors will describe the objectives of and methodology utilised during the

“Small Group Learning in Real

Property Law” project and report on

the benefits and difficulties which both students and teachers encountered. The

results

of the authors’ empirical study will be analysed and when

necessary their own observations added. Case studies will be used

to illustrate

and support these findings. Finally the authors will reflect upon the

implications flowing from the data and draw some

conclusions regarding the

efficacy of small group learning in legal education.

OBJECTIVES

Jaques asserts that:

Teaching and learning in small groups has a valuable part to play in the all

round education of students. It allows them to negotiate

meanings, to express

themselves in the language of the subject, and to establish a more intimate

contact with academic staff than

formal methods permit. It also develops the

more instrumental skills of listening, presenting ideas and

persuading.6

The authors viewed the small group as

the ideal medium through which to achieve their goals in Property Law. It would

provide the

students with an opportunity to work and interact with one another

in small teams and to provide mutual support. As it was envisaged

that the group

tasks would have an oral as well as a written component, provision would be made

for different learning styles.

It was anticipated that administering and

guiding the groups would be particularly challenging given that 435 students

were enrolled

in the course. However it was thought that the ultimate benefits

for the students would far outweigh the daunting temporal demands.

THE PROJECT

The project was comprised of two components: Self-Learning Groups and

Research Assignment Syndicates.

The tutorial group was used as the vehicle

for the project. Tutorials in Property Law were conducted weekly. Each tutorial

group was

comprised of approximately 24 students. In previous years students had

been encouraged to form small study groups voluntarily from

within their

tutorial groups. These groups, known as Self-Learning Groups

(‘SLGs”), met fortnightly and discussed problem-based

material

provided by the Property teachers. The authors formally divided each Property

Law tutorial group into SLGs of four to six

students. Students were required to

register for an SLG and were given the opportunity either to form their own

group or to be placed

in a group with others they did not know. Prior to

registering students were advised that the SLGs would take collective

responsibility

for 30 per cent of the assessment of each student in

the SLG.

Self Learning Groups

A booklet was prepared with tutorial and SLG

problems, similar to examination questions and divided into weekly segments.

Topics corresponded

to those in the subject reading guide issued to all Property

Law students at the beginning of the year. Each SLG was expected to

meet weekly

at a time and place of its choosing to discuss the week’s problems. As the

problems were on the same topic as those

covered in the weekly tutorials it was

intended that the SLG material would supplement and reinforce the subject matter

covered in

that week’s tutorial.

During the course of the year, each

SLG was required to present two problems from the booklet to their tutorial

group, one in each

semester. The authors allocated the problems and each member

of the SLG was expected to contribute to both the preparation and discussion

of

the designated problem. Presentations were of approximately 15 minutes’

duration.

Assessment took into account each student’s tutorial

attendance (one per cent) and contribution to class discussion (one per

cent) as

well as preparation for and presentation of the two problems (three per cent), a

total of five per cent. Given the number

of components that made up this five

per cent assessment, it was highly unlikely that each member of the SLG would

receive an identical

mark. The minimal mark allocation for each component was

seen as an educational tool, encouraging students to attend tutorials and

to

participate in class discussion. Attendance at tutorials was not compulsory, but

a record of attendance was kept for each tutorial

group. This record indicated a

marked increase in student attendance at tutorials compared to previous

years.

Research Assignment Syndicates

It was intended that the SLGs would form the basis of

Research Assignment Syndicates (”RAS”) of four students. A number

of

those SLGs with four members automatically formed an RAS. Those students who

particularly requested to work with others who were

not in their SLG were

accommodated, provided that any “spare” members of the SLG were

accounted for. In the interests

of a harmonious working relationship between

members, in some cases the RAS were comprised of students across tutorial

groups.

In another extensive administrative exercise, the authors regrouped

the “spare” members as well as the SLGs with more

than four members

into syndicates7 of four for the purpose of completing

the research assignment. In a small number of cases, having regard to group

dynamics or to

preserve an SLG, syndicates of three or five were formed and on

two occasions special permission was granted for syndicates with

only two

members.8

There were two components to the research

assignment: a research strategy report, worth five per cent, describing research

methodology

and skills and a 2,000–2,500 word written assignment worth 20

per cent. The criteria for assessment of the written assignment

were content,

presentation, analysis and other legal skills. The students were required to

undertake the research work in their syndicates

of four, but were permitted to

write and submit the assignment either as a group of four or in pairs.

Learning objectives

One of the main motivational factors for introducing

small groups was the recognition of the importance of cooperative working among

peers with the resultant enhanced communication skills and tolerance of

divergent points of view. While these skills and attributes

are not specific to

Property Law and are important throughout the Law course, the authors saw the

project as an opportunity for the

creation of invaluable qualities and skills

that would help to equip students for life in addition to enhancing their

studies of

Property Law.

Some students may be intimidated by the prospect of

speaking in front of a large group but feel more confident about offering their

thoughts to a small group. Such an environment can also fulfil a desire for

social belonging, fostering motivation and learning.9

Students’ ability to “feed off” one another has both

positive and negative connotations. It encourages the sharing

of ideas and

drawing of inspiration from one another. The authors envisaged that the

convivial environment of the SLG would create

the appropriate forum for an

exchange of ideas and reflection on the problematic areas of Property Law. This

would in turn assist

students in their comprehension and appreciation of this

particularly difficult area of law. Those students who preferred working

on

their own could use the group setting to ventilate ideas and then consolidate

their views individually. A task might be divided

into a number of components:

for example, research, writing, proof reading and consolidation of the final

product. Each step can

draw on the particular skills of different members and

the end result is vastly superior to that which the individual member could

produce in isolation.

On the negative side, the authors envisaged a potential

problem with “freeloaders”10 and the

“outsider”. The code of ethics and work program were intended

largely to circumvent this issue.

Code of Ethics

Once assignment topics became available RAS members

were expected to conduct a preliminary meeting and design a code of ethics and

work program. This document was to be submitted to the Faculty by a specific

date. Students were encouraged to discuss difficulties

within the group with the

authors. A procedure was designed for use by syndicates experiencing problems

with a member who did not

comply with the RAS' code of ethics or work plan. The

participating members would be required to complete and sign a standard letter

setting out the breach and advising the non-participating member of expulsion.

The letter would then be posted to the non-participating

member and a copy given

to the authors. Subject to compliance with that procedure by a specified date,

an RAS would be authorised

to regard the non- participating student as no longer

being a member of the syndicate. That student would be required to submit a

separate assignment on the same topic independently and the expulsion itself

would not constitute grounds for special consideration

or an extension of

time.

Each member of the RAS was required to sign a written declaration

certifying that they either had or had not made a relatively equal

contribution

to the preparation and writing of the assignment and that they would accept an

identical mark. In the case of those

who certified that an equal contribution

had not been made an explanatory letter would be required to accompany the

declaration.

Interestingly no students availed themselves of this procedure

although the research indicates (see RAS difficulties below) that 10

per cent of

the students who responded to the questionnaire perceived that there had been an

unequal contribution from their syndicate

members. This is supported anecdotally

as a few students complained informally after having submitted their assignment

that some

group members had not contributed equally to the work and asked for

this to be taken into account in the assessment of the assignment.

Apart from

pointing out to students the important ethical lesson11

that they should not sign a declaration unless they believed in its truth, there

was nothing that could be done at that stage.

It

seems from this anecdotal information that the students in question were not

prepared to compromise 25 per cent of their assessment

by raising the issue

before submitting their assignment but were prepared instead to make a moral

compromise in making the declaration.

Other students may have had different

reasons for deciding not to declare and explain an unequal contribution, but

this information

did not emerge from the project.

Methodology

Throughout the project, it was intended that the

authors would evaluate the ongoing progress of the SLGs and RAS. After all

groups

had completed both tutorial presentations and the research assignment, a

detailed questionnaire was designed with the help of Monash

University’s

then Centre for Higher Education Development (CHED)12

and administered to Property Law students. 268 of the 435 students enrolled in

the subject, that is approximately 62 per cent, attempted

the questionnaire

which had separate sections relating to SLGs and RAS. The questionnaire was

voluntary and anonymous.13

The questionnaires were

administered with a view to improving student learning and the authors’

teaching as well as generating

ideas for alternative course presentation and

different teaching methods that would aid and enthuse students in their study of

Property

Law. The main aims of the questionnaire were to ascertain whether:

- law students prefer, enjoy and perceive a benefit from learning in small groups;

- law students benefit from teamwork and interaction with other students and

- specific strategies should be developed to assist with small group/team based learning to cater for different learning styles.

The questionnaire consisted of

17 straightforward questions divided into the two sections, relating to SLGs and

RAS respectively,

intended to ascertain student attitudes towards small group

learning in the two contexts.

Unfortunately, resources did not extend to

allowing the authors to obtain further qualitative research from student focus

groups.

Research Findings

When canvassed informally in tutorials prior to

experiencing small group learning in Property Law, many of the students seemed

to

have a positive view of working in small groups for tutorial presentations.

However, fewer students seemed to feel positive about

completing the research

assignment in groups.

Following completion of the formal questionnaire the

responses were analysed and produced some interesting results.

Self Learning Groups

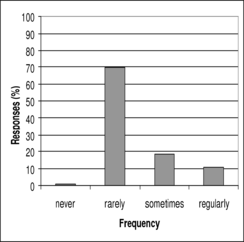

The success of the self-learning group/tutorial project depended to a large degree on the frequency with which the groups met. Of the 252 students who responded to this question, only 27 (10.71 per cent) stated that they met regularly, on average once a fortnight. Of those who met more than twice during the academic year all group members attended meetings in only 56.76 per cent of cases. This figure would seem to be indicative of the logistic difficulties that students encountered and may serve to explain why generally the SLGs met infrequently. The benefits and difficulties encountered by the students are examined in further detail below.

Chart 1: Frequency of SLG Meetings

As shown in Chart 1, 70 per cent of the students responding to this question

met only rarely, that is one to four times during the

year, which suggests that

a number of SLGs may have met only to prepare their two tutorial presentations.

If so, this would seem

to reinforce the importance of assessment as a motivating

factor in the success of group working.14

However,

it is interesting to note that 79 per cent of the respondents thought that each

member of the SLG should receive an identical

mark for the tutorial

presentation. The most striking reasons for this conviction were:

- Group effort: 27 per cent believed that as the group had worked as a team, a group mark was required. If marks were not identical it would defeat the purpose of the SLG or the SLG would not work well. There was overall recognition that portion of what is assessed is the ability to work as a team.

- Equality: 19.5 per cent considered that each SLG member had contributed equally and thus it was essential that all should receive identical marks, even if they had completed their work individually. “Freeloading” was regarded as having played an insignificant part in the workings of the group and if it existed was insufficient reason for members to be allocated different marks.

- Differing contributions: By way of contrast, there seemed to be a significant concern among respondents (17.5 per cent) that as the tutor/assessor was unable to determine how much work each individual member had done behind the scenes, it was only fair that all members of the group should receive the same mark. Conversely, 12.5 per cent of respondents indicated that the only way to resolve differing contributions was for students to receive separate marks.

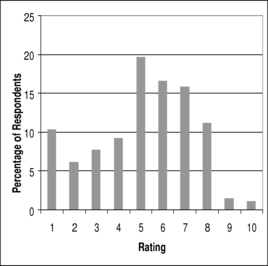

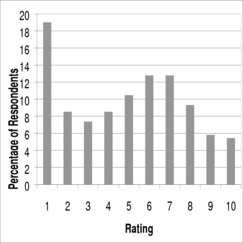

When asked how they rated working in SLGs on a scale of one to ten, ranging from not helpful to extremely helpful, 10.5 per cent of respondents had strongly negative feelings about working in SLGs and only 2.7 per cent found the groups extremely helpful. However, a majority of students indicated that they found SLGs helpful: 73 per cent designated a rating between four and eight on the scale, with a noticeable concentration between five and eight. (See Chart 2.)

Chart 2: Rating for SLGs

Division of work and co-ordination of the presentation

The students were asked to describe the method that

their SLG adopted for the allocation of work and co-ordination of the oral

presentations.

All students had been required to participate actively in the

presentation, but each group had been able to decide the basis on which

work

would be allocated to its members. Of those who provided information in response

to this question, some indicated the frequency

with which work was divided,

varying from 35.5 per cent who said that work was always divided among the

SLG members to 6.5 per cent

who stated that work was never divided up but was

undertaken individually. Other respondents described the basis on which work was

divided, for example to ensure equality of division, to accommodate group

members’ “comfort zones” or according

to the issues identified

in the problem. Yet others described both the frequency with which and the basis

on which work was allocated.

Observation of the presentations themselves

suggested that some SLGs had divided the preparation and presentation according

to the

different skills and learning styles of the group members.

While it

was disappointing that 12.3 per cent of the respondents allocated the work

haphazardly according to which SLG members were

present at the meeting at which

the division was made, it was pleasing to note the degree to which the students

were concerned to

ensure equality and satisfaction for all members of their

SLG.

Benefits

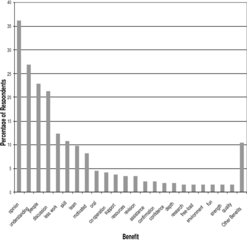

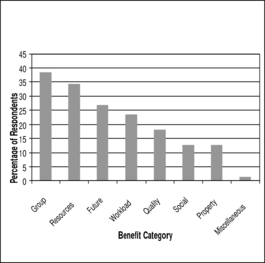

Respondents indicated that they derived a number of benefits from the experience of working in SLGs, 87 per cent finding at least one benefit associated with SLGs. Nine per cent of respondents left the question blank and only four per cent found no benefit.

Chart 3: SLG Benefits

The significant benefits were:

- Sharing of opinions/information and understanding: A clear majority (62 per cent) of respondents benefited from the sharing of opinions and information, listening to fellow students, pooling resources and group discussion.15 Their understanding of the material increased as a result of exchange of ideas and depth of discussion. Certain parts of the course were reinforced and revised and tutorials were more meaningful.

- Skills: Some

students noted an increase in their level of confidence and 34 per cent of the

respondents reported that they had acquired

one or more new skills

including:

- - Interpersonal skills including the ability to communicate, compromise and co-operate with other group members. Recognition of different learning styles and abilities in some cases resulted in frustration management.

- - Problem solving skills including the ability to analyse a question, synthesise material and solve a legal problem.

- - Enhanced study techniques such as work method, organisation and self-discipline.

- - Improved oral communication skills, including listening.

- - Teamwork, including co-operative learning and collective thinking.

- Interaction: 24 per cent found group working a fun and enjoyable experience, benefiting from the social and academic interaction, meeting new people and the creation of a network of other Property Law students.

- Workload: 16 per cent appreciated the reduction in workload and responsibility as a result of sharing.

- Motivation: Realisation of the interdependence of group members resulted in increased motivation among eight per cent of respondents. This motivation inspired preparation, organisation and work that would otherwise not have been done.

Difficulties

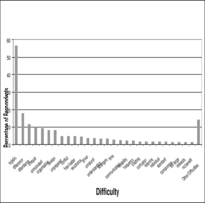

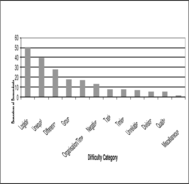

Ninety two percent of the respondents experienced at least one difficulty while working in an SLG. Difficulties ranged from “A greater risk of getting the answer wrong because there was no supervision” to “having to work at a group pace eg earlier or slower than would normally do work”. On analysis of the data the most frequently recurring difficulties fell into a number of categories in the following descending order:

- Logistics, including finding meeting times, getting the group together and juggling timetables and other commitments, were problematic for 56.7 per cent of respondents.

- Attendance, including lack of motivation, was an issue for 21 per cent of respondents. Not all group members attended SLG meetings or the tutorial presentations or, if they attended, were very late. This suggested that group members had different levels of commitment that permeated throughout the meetings and tasks.

- Differences, including differences of opinion, disagreements about the approach to be taken and an inability to reach a consensus, troubled 18 per cent.

- Unequal contributions to the work of the group were also mentioned. However, given the potential for inequality, this is particularly interesting as it ranked fourth in the list of difficulties and was mentioned by only some 10 per cent of respondents.16 In fact ‘freeloaders’ received criticism by only 4.85 per cent.

- Organisation and division of work were a challenge for some nine per cent of respondents. Some of the SLG problems allocated were considered to be of insufficient magnitude to allow each member of larger SLGs to participate equally and some students found difficulty in co-ordinating their presentations, resulting in time wasting and lack of efficiency.

Chart 4: SLG Difficulties

Research Assignment Syndicates

One hundred and ten syndicates were formed for the

research assignment. Interestingly, even though students were able to choose the

members of their RAS, only 51 per cent of respondents indicated that they chose

all RAS members with a further seven per cent choosing

some members. The

remaining 42 per cent were allocated to an RAS with other students in their

tutorial group.

Separately, students were asked whether all members of their

RAS and SLG were identical. Notably, 48 per cent of respondents reported

that

they were not and that students from different SLGs made up the RAS. Of those,

34 per cent would have preferred to be in an

RAS with members of their SLG

whereas 54 per cent would not and 12 per cent were undecided. Of those undecided

students, the majority

(62 per cent) were of the opinion that the composition of

the group made little difference.

Of those respondents who indicated a

preference for a syndicate comprised of their SLG members the main reasons given

were familiarity

with members and logistic arrangements.

The students were

also asked how they rated working in a RAS, again on a scale of one to ten

ranging from not helpful to extremely

helpful. It is interesting to note that

the distribution of ratings for RAS was significantly different from that for

SLGs. A smaller

majority indicated that they found the RAS helpful: 11 per cent

of respondents found RAS extremely helpful while at the other end

of the scale

19 per cent exhibited extreme dissatisfaction with group work in this form. The

other 70 per cent were spread more evenly

along the scale between two and nine.

The mean of 4.92 indicates that the student respondents had a negative reaction

to the RAS

and did not regard them favourably (see Chart 5.)

Chart 5: Rating for RAS

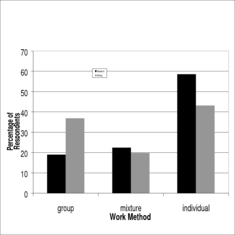

Division of Research and the Writing of the Assignment

Only eight per cent of respondents stated that they worked as a group for both the research and the writing of the assignment and read all the material and understood all aspects through collaborative discussion. Greater numbers worked in groups either for the research or the written components separately. Nineteen per cent of respondents combined in their RAS for researching the assignment whereas notably 37 per cent wrote the assignment in groups. Fifty nine per cent of respondents researched individually and 43 per cent wrote up the assignment on their own: in some cases one person alone reported having written the whole assignment and in others all members wrote separate sections that were then merged together. The balance of the respondents combined group and individual work throughout (Chart 6).

Chart 6: Research/Writing

The student respondents described five main criteria for the division of assignment responsibilities and work:

- Issue: 34.6 per cent made the division on the basis of the issues identified in the assignment question, including jurisdiction, or according to primary and secondary source material.

- Comfort: 21.5 per cent based their allocation on what they felt most comfortable doing, personal preferences, the demands of their other commitments or the perceived strengths or competencies of the group members.

- Equality: 15 per cent endeavoured to ensure an equal division of labour.

- Task: 15.4 per cent allocated different tasks to different group members. In some instances the allocation was made according to the nature of the task.17 In other instances task allocation was driven by other commitments such as work, overseas travel and assessment requirements in other subjects.

- None: a disturbing 12.3 per cent again haphazardly divided the work with no organisation and according to which group members were present at the initial RAS meeting.

Code of Ethics

Students were asked whether their RAS had adhered to its code of ethics: 69 per cent of respondents stated that they did while 31 per cent stated that they did not. Those who did not adhere to the code gave the following main reasons:

- Irresponsibility: 25 per cent said that despite the code, some members of their group refused to be accountable and responsible to the group;

- Priorities: 17 per cent noted that some RAS members gave the research assignment a lower priority than other activities, for example other assessment, work and travel, which made it impossible to enforce the code;

- Other reasons included initial expectations being unrealistic and the complaint procedure being perceived as ineffective.

Of those respondents who did adhere to their code of ethics, 38 per cent found it to be a useful tool in group dynamics. The reasons offered for the utility of the code overlapped to some extent with the reasons given in relation to adherence. The main reasons articulated were:

- Incentive (16 per cent): The code ensured that all group members did equal work, refrained from “slacking off” and made members consider their responsibilities to the group and give thought to potential problems before commencing the project;

- Guideline (12 per cent): The code provided a guideline to which members could adhere and they knew and understood what was expected of them. It could, and in some cases was, used as a tool to resolve disputes between members. The preparation of the code also provided an introductory session in working together as a group for those RAS that were not from the same SLG.

- Moral obligation (two per cent): All members had contributed to and had agreed with the code and so felt obliged to follow it and were made accountable for their performance;

- Efficiency (one per cent): As a result of group working, division of labour and collaborative discussion as agreed in the code, the project was completed more efficiently and effectively.

Conversely, 62 per cent of the respondents who adhered to the code found that it was not useful.18 The main reasons for this conclusion were:

- Irrelevant and unnecessary (32 per cent): Some students considered the code to be a formality and submitted one only because it was compulsory. The tenor of the responses indicated that the students would have acted or reacted in exactly the same way with or without a code of ethics.

- Not adaptable or unworkable: The code was found to be easy to write before the project but difficult to adhere to in practice. It was too general for the specific type of problems encountered. New circumstances that arose during the project meant that part or all of the code was irrelevant.

Benefits

The majority of respondents found at least one benefit in working in an RAS. Eight per cent could find no benefits and were left with only negative feelings towards group working and a further 15 per cent failed to give any response. For the 77 per cent who responded positively, the main benefits of collaborative working included:

- Group:19 38 per cent benefited from a number of aspects of working with other people including discussion, support, teamwork, group responsibility and co-operation.

- Resources: 34 per cent found that the group had more resources available to them combined than individually in terms of ideas, opinions, perspectives, research ability and writing ability.

- Future: 27 per cent gained something from the group work that would benefit them in the future, including interpersonal; academic, working and organisational skills and confidence.

- Workload: 24 per cent appreciated the reduction in workload as a result of sharing.

- Quality: 18 per cent considered that the quality of their group assignment was better than an individual assignment would have been.

- Social: 13 per cent found the experience to have a social element. They got to know new people, met other students and made new friends. Working in syndicates was an enjoyable experience for them.

- Property: 13 per cent considered that the experience had increased their understanding of Property Law. They learned from other members, a broader knowledge base was created and they realised their weaknesses in the subject. An additional bonus for some was the good mark they received in the subject.

Chart 7: Benefits of RAS

Difficulties

Disappointingly only one per cent of respondents expressly stated that there were no difficulties associated with working in an RAS whereas 91 per cent listed at least one difficulty. The six most prevalent difficulties were:

- Logistics: As with SLGs logistic obstacles headed the list of problems. Fifty-one per cent of respondents encountered difficulty finding suitable meeting times and venues and co-ordinating all the members of the group. Inability to communicate was a major difficulty, as some students did not have email access.

- Group Dynamics:

46 per cent of respondents found difficulty working harmoniously and as one unit

rather than as individuals. A number

of reasons were offered for this high

figure:

- - Students were unable to work at their own pace and at times that suited the individual. Group working slowed down the pace and they found they had to spend more time than they would have on an individual project.

- - The differences of opinion, writing styles and approaches caused severe constraints in delivering what some students considered a decent end product. Individual work resulted in a fragmented assignment.

- - In some instances where the RAS was not the same as the SLG, to begin with the members did not know each other and found difficulty working with relative strangers.

- - The interaction between members was at times strained as there was an expectation that members would be polite to one another and diplomatic in their criticisms so as not to offend a fellow member.

- - The inability of the group to accept the views of one member and having to compromise with the group on an issue about which a member felt strongly created negative feelings, stress, migraines, loss of self esteem, personality clashes and regrettably loss of friendships.

- Inequality: An

interesting result, and more in accordance with expectations (unlike the SLG

response), was that 40 per cent of respondents

found difficulty in motivating

all the members to contribute equally and at the same standard. The problems

encountered included:

- - Some members of the group were described as lazy and unmotivated. There were different perceptions of the amount of work involved and the standard of work required.

- - Some students had a clash of commitments and were not always prepared to put the RAS first.

- - The absence of individual assessment meant that some students did the work of others and all members received identical marks whether they deserved it or not.

- - Some students realised they had not contributed equally, resulting in feelings of guilt.

Chart 8: RAS Difficulties

CASE STUDIES

The following case studies illustrate some of the different group dynamics, attitudes and challenges that were evident among the RAS during the project.20

|

Case Study 1 Anh, Bella and Charlie are three students who all embarked on their Law

studies as school leavers and are also friends. They attended

the same Property

Law tutorial group and formed an SLG. Digby, a mature age student with other

responsibilities in addition to study,

was added by the project co-ordinators as

the fourth member of the SLG. The members of the SLG also constituted an RAS.

The members

of the group worked well together for their first oral presentation

but encountered difficulties with the research assignment. Prior

to commencing

work on the assignment, the students had completed a code of ethics setting out

their work plan and ethics.

However, once work started, the younger students expressed concern about Digby’s participation, claiming that he did not attend group meetings or arrived late and that if he did complete his share of the work, it was not of an acceptable standard. In turn, they found him to be critical of their contributions. The three younger students seemed anxious that Digby’s perceived lack of commitment would affect the final product and assignment result. An attempt was made by Property teachers to mediate between the parties and they were encouraged to discuss the perceived difficulties. However, unfortunately the situation deteriorated and it became obvious that the other three students no longer wanted Digby as a member of the RAS. These feelings were not mutual and he wanted to remain in the RAS. Co-operative work became impossible and the expulsion procedures were utilised. Digby was offended when he received the expulsion notice and thought that the other group members could have been more understanding of the other demands on his time. He considered it to be unfair that he was then obliged to submit an assignment on his own. However, it had not been possible to resolve the matter amicably within the time constraints for submission of the assignment. The final tutorial presentation was made as a “group” but it was apparent that there were tensions and the group was fragmented three:one. |

Comment

This example of some of the challenges of group work illustrates

the fact that, while “group work can have a positive impact

on students in

a variety of ways”,21 it can lead to conflict

between members and can have a negative impact on some

students.22 While their concerns may have been

legitimate, it is also possible that the younger students were abusing the

expulsion procedure

and that the mature age student was treated unfairly.

Was

there a better way to handle the situation? Could the authors have supervised

the implementation of the work plan and group meetings

and overseen the work to

make sure everyone was contributing fairly? This was considered to be too

intrusive and as defeating the

purpose of team work and group learning. The

authors were also conscious of the importance of the students taking

responsibility

for their own learning. Another consideration was the

“domino effect” and how other syndicates having difficulties would

respond to this intervention. Furthermore, it was considered that it would be

resource intensive and time consuming; the time could

be spent more productively

in other ways.23

|

Case Study 2 Emilia and Fergus were friends but, due to time- tabling, were in different

tutorial groups. They requested that they be in the same

RAS but had no

preference for the other two syndicate members. Gilda, a full-time student, and

Hans, a mature aged, part-time student,

were added to complete the

syndicate.

Shortly after the group’s code of ethics had been finalised, work commitments sent Hans out of the metropolitan area. While the authors were made aware of the situation, the other members of the RAS decided they could communicate with Hans by telephone, email and facsimile transmissions to complete the assignment. Unfortunately, however, Gilda suffered a succession of health problems and was unable to keep pace with group commitments. The syndicate made every effort to include her but eventually approached Property teachers with the problem. In the circumstances it was decided not to use the formal expulsion procedures. Gilda was given permission to submit a separate assignment and was also granted special consideration. The long distance arrangement worked for the remaining syndicate members and Emilia, Fergus and Hans submitted a combined assignment. |

Comment

Again there were challenges, but this RAS should be viewed as a

success. The fact that the long distance working relationship succeeded

is a

tribute to the determination and commitment of the three remaining RAS members.

One must question, what was the bonding factor?

The two initial group members

were friends, but apart from the code of ethics and work plan and the fact of

having been placed with

Gilda and Hans they owed the other two RAS members no

allegiance. Arguably it would have been easier for them to break away and submit

their own assignment. However they chose not to and they worked to complete the

assignment under difficult conditions.

Gilda’s situation was handled

with as much sensitivity as possible. With the additional time and special

consideration, she

was able to complete not only the assignment but also the

subject Property Law that year. Were it not for the other group members,

staff

may not have been aware of the difficulties and she may simply have

“dropped out” of law school.

|

Case Study 3

Imran, Jasmine, Katerina and Lee were long-standing friends in the same

tutorial group who formed an SLG and RAS. While the students

were in the throes

of their research assignment, a member of Imran’s family became critically

ill. It was difficult for him

to concentrate effectively on the task at hand and

he foreshadowed a possible request for an extension of time. The other members

of the group made a joint decision to support Imran unconditionally. They

provided him with both practical and moral support and

the assignment was

submitted on time.

This syndicate received a high mark for their work. The assessor had no idea of the history behind the assignment. The group members remain friends. |

Comment

This is an example of group work at its best. Left to his own

devices Imran may not have submitted an assignment on time, if at all,

and it is

unlikely that the work would have been of the same quality. However, with the

support and assistance of his friends and

fellow RAS members, the assignment was

completed to a high standard and all were very happy with the result.

Does

this mean that a foundation of existing friendship is necessary for a successful

small group or can group members who did not

know each other previously develop

the necessary skills to cope in such a situation? While friendship was

apparently an important

factor in Case Study 3, Case Study 2 suggests that a

small group can operate successfully in other circumstances. The team

environment

allows for the development of peer support, cooperation and

collaboration, providing reciprocal and mutual benefits for all members.

REFLECTIONS

Expectations

When the idea of small group learning was introduced to students, the

information provided was sparing and in general

terms.24 With hindsight, and with the benefit of the

insight provided by the case studies,25 it would have

been preferable for additional and more specific information to be available to

students to provide them with a firmer

foundation for drafting of a more

detailed code of ethics and for better mental preparation for the tasks

ahead.

Apart from division of the tutorial groups into SLGs and RAS as

described above, minimal structure and direction was provided for

the students.

The students were given the independence, responsibility and flexibility to

co-ordinate the frequency and modus operandi

of their own group meetings.

Feedback was provided to students about the content of their research

assignments and group presentations. However, the authors offered

little input

about or evaluation of the groups’ working as a team or the division of

tasks. Students were thus offered little

guidance on how to operate within the

group rather than as an individual, but generally seemed to develop the teamwork

skills required.

Interaction

The authors believed from the outset that in order

for groups to work effectively a “bonding factor” is required.

Generally,

one cannot group four strangers and expect them immediately to bond

and work together.26 The students “must connect

to form an effective working group”.27 Therefore

the SLGs were formed to allow the students to become acquainted and develop a

working relationship in preparation for their

tutorial presentations and

especially for their research assignments. Unfortunately, however, some of the

SLGs met on only one occasion

prior to combining for an RAS and in other cases

students were in an SLG and RAS comprised of different members. The number of

SLGs

that did not team up as an RAS but elected instead to undertake the

research assignment with other students surprised the authors.

Case Study 3

illustrates that years of friendship can be one of the bonds that holds a group

together, both as an SLG and as an RAS.

Case Study 2 is more puzzling: perhaps

one can attribute the cohesiveness of the group to a moral bonding founded on

the code of

ethics in addition to the development of interpersonal and

communication skills.

Apart from those few groups in which the expulsion

procedure was utilised, having completed the research work as a whole group the

vast majority of RAS chose to continue with the writing and submission of the

assignment also as a whole group. Notably only three

syndicates elected to

divide into pairs for the writing and submission of the assignment.

In

addition to the interaction that the students described in their responses to

the questionnaire, the authors also observed other

features. In particular, it

was noticeable that some of the SLGs sat and socialised together in tutorials,

either as a whole group

or as part of a group. This occurred regularly for some

groups and occasionally for others. In some instances this started from the

beginning of the year as the students were already on friendly terms and had

formed their own SLG, but in other instances this was

a phenomenon that

developed as the year progressed and the students became better acquainted and

developed their interpersonal skills.

The social aspect of small groups is

recognised as an important factor in enhancing

learning.28

Similarly, the authors also observed

some apparent difficulties that were not mentioned in the responses to the

questionnaire. Students

were allocated to SLGs (and RAS) without regard to

gender or age, with the result that there were different proportions of male and

female or mature-age and younger students in different groups. Generally this

did not cause any problems, but Case Study 1 illustrates

some of the tensions

that arose when expectations and other commitments differed between a mature-age

student and the other group

members who were younger. In one

group29 of three female students and one male student

tension developed along gender lines during the preparation and writing of the

assignment

and this carried over into the SLG and was apparent in tutorials. In

other examples, students requested tutorial changes on the basis

of alleged

timetable changes, but it appeared that the real basis was difficulties within

their SLG.

Learning

Pedagogically the small group, team based approach is a sound one. As the respondents reported, it provides students with an opportunity to share information, opinions and ideas through in depth discussion as well as to interact and communicate with one another in an environment of mutual support. This co-operation and pooling of resources in turn can lead to a greater understanding of the subject matter and improved study techniques and problem solving skills. Students can also acquire or develop interpersonal skills including the ability to communicate, compromise and co-operate in a group.

Self Learning Groups and Research Assignment Syndicates: Comparisons and Contrasts

There was some commonality between the top SLG and

RAS benefits identified by the students: sharing of opinions and discussion;

sharing

of workload; acquisition of interpersonal and academic skills; social

interaction; and increased understanding of Property Law. The

difficulty that

stands out for both forms of small group work is logistics and is one of the

variables encountered in group work

that are generally beyond the control of the

teacher.30

However, overall students had a more

positive view of SLGs than the RAS. Perhaps the relative weighting of these two

components of

the year’s assessment was significant. While only five per

cent was attributable to tutorial participation and the SLG oral

presentations,

it was apparently enough to induce the students to participate in their SLG at

least twice throughout the year. The

more motivated students, perhaps in more

successful groups, met more frequently and arguably experienced more of the

benefits of

small group learning.

The RAS were a different matter and

elicited more extreme reactions from the students. The authors believe that an

important factor

in this was the relatively large proportion of the year’s

assessment that depended on the performance of the RAS. As the case

studies

show, this brought out both the worst and best in syndicate members.

SOME CONCLUDING COMMENTS

Le Brun and Johnstone describe “[t]he consequences of commodifying

education” and the potential drawbacks to which this

exposes the

university system.31 A delicate balance is thus

required between pedagogical considerations and catering to student

demands.

After considering the research findings and student reactions and

affirming the “Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate

Education” with which this article commenced, the authors are of the

opinion that it is worth continuing with and promoting

SLGs but not

RAS.

Notwithstanding the benefits of the RAS identified by respondents, in

light of the nature of the difficulties experienced and the

relatively high

proportion of the students’ annual assessment attributable to this

component and given that the average reaction

was negative, it is hard to

justify the continued use of the RAS. Conversely, despite the range of

difficulties associated with the

SLGs, in light of the nature of the benefits

gained and given that the average reaction was more positive, the authors

believe that

SLGs should continue.

However, given that administering SLGs and

oral presentations is also extremely time consuming and resource intensive, it

may not

be feasible to maintain small group learning in the form described. Even

if it is not possible to continue with SLGs on a formal

basis, students of

Property Law are still encouraged to form and work in SLGs informally as

before.

The authors remain committed to promoting the benefits of small group

learning and fostering an environment in which co-operative

and collaborative

learning32 are

encouraged.33

* Lecturer in Law, Monash University.

** Assistant Lecturer in Law, Monash University.

This research was supported by a Monash Law

Teaching Innovations Fund Grant, which is acknowledged gratefully. The authors

also gratefully

acknowledge the invaluable assistance provided by their research

assistant, Jennifer Whincup in the collection and analysis of data

for this

article.

©2003 (2002) 13 Legal Educ Rev 189.

1 GF Hess & S Friedland, Techniques for Teaching Law (Durham, North Carolina: Carolina Academic Press, 1999) 15-16.

2 A Greig, Student-Led Classes and Group Work A Methodology for Developing Generic Skills [2000] LegEdRev 3; (2000) 11(1) Legal Educ Rev 81.

3 Students have usually completed the core subjects of Legal Process and Criminal Law and Procedure and have either completed or are undertaking concurrently the core subjects of Contract and Torts.

4 Leveson, for example, notes that there is “no unambiguous definition of small group work” but that “there is general agreement that effective small group teaching and learning is student-centred”. L Leveson Small Group Work in Accounting Education: an evaluation of a programme for first-year students (1999) 18 (3) Higher Education Research & Development 361, at 362. Gerlach states that “Collaborative learning is based on the idea that learning is a naturally social act in which participants talk among themselves. It is through the talk that learning occurs.” JM Gerlach, Is This Collaboration?, in K Bosworth & S Hamilton eds, Collaborative Learning: Underlying Processes and Effective Techniques (1994) 59 New Directions for Teaching and Learning 5, at 8.

5 McInnis observes that “What makes a small group is the nature of the process of teaching and learning that takes place. Small group teaching is essentially a highly active learning experience for all participants, and assumes that students clarify their thoughts by talking.” C McInnis, Small Group Discussions, at Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Melbourne, <http://www.cshe. unimelb.edu.au/teachlearn1.html> (last accessed 22/09/02) (copy on file with authors).

6 D Jaques, Learning in Groups, 2nd ed, (London: Kogan Page,1991) 9.

7 Le Brun & Johnstone describe syndicates as “small, teacherless groups of four to six students. Students are set a clear task, topic, or problem, and then left to analyse and synthesise the relevant material or solve the problem on their own but within a supportive group environment.” M Le Brun & R Johnstone, The Quiet (R)evolution: Improving Student Learning in Law (Sydney: The Law Book Company Ltd, 1994) 294.

8 In one instance the two students wished to complete the research assignment early due to overseas travel plans and in the other instance the two students had special study needs.

9 Le Brun & Johnstone, supra note 7, at 292

10 Slavin emphasises that, while co-operative learning has potential benefits, it “can allow for the ‘free rider’ effect, in which some group members do all or most of the work (and learning) while others go along for the ride. The free rider effect is most likely to occur when the group has a single task, as when they are asked to hand in a single report ...”. RE Slavin, Cooperative Learning: Theory, Research and Practice 2nd ed (Massachusetts: Allyn & Bacon, 1995) 19.

11 Le Brun & Johnstone contend that “If we do not emphasise the ethical aspects of law to our students, they may fail to see the parameters of moral action in the practice of law. The more aware our students are of the moral content of the law, the more likely they will behave more appropriately.” Le Brun & Johnstone, supra note 7, at 397.

12 CHED is now the Higher Education Development Unit (HEDU) of Monash University’s Centre for Learning and Teaching Support (CeLTS).

13 As the questionnaire was voluntary and anonymous, it is not possible to determine how many SLGs and RAS were represented by the individual respondents. It should also be noted that not all respondents provided an answer to every question.

14 “Assessment is the most powerful lever teachers have to influence the way students respond to courses and behave as learners.” G Gibbs, Using Assessment Strategically to Change the Way Students Learn, in S Brown & A Glasner eds, Assessment Matters in Higher Education (Buckingham: Open UP, 1999) 41.

15 Leveson notes that “Discussion facilitates learning, not only because it is an inherently motivating activity but also because the very process of helping others is one of the best ways of learning.” L Leveson, supra note 4, at 363.

16 This contrasts with the finding by Zariski in a survey of Law students undertaking group work that 83 per cent of respondents stated that all group members had not contributed equally to the project. A Zariski, Lessons for Teaching Using Group Work from a Survey of Law Students, in R Pospisil & L Willcoxson eds, Learning Through Teaching 361-66, Proceedings of the 6th Annual Teaching Learning Forum 1997 (Perth: Murdoch University, 1997). However, Zariski’s survey asked the students directly in question 27 to tick “yes” or “no” in response to the statement that “My experience of group work has been that all group members contribute equally to the project” whereas the questionnaire in this study asked students more generally in question 3(b) to list three difficulties experienced while working in an SLG.

17 For example, in one group two members did the research, one wrote a draft and the remaining member edited the assignment.

18 This suggests that there may be a need for guidelines or examples to assist students in understanding the purpose of and then drawing up a code of ethics.

19 Zariski also found that, of the objectives of the course co-ordinators in setting group work, the three that the student respondents regarded as most relevant to them were co-operation, dispute resolution skills and organising. Zariski, supra note 16, at 364.

20 The names and some personal details have been altered to preserve anonymity.

21 A Zariski, Positive and Negative Impacts of Group Work from the Student Perspective in Murray-Harvey and Silins eds, Advancing International Perspectives, Proceedings of the Higher Education Research and Development Society, Volume 20 (Adelaide: Higher Education Research and Development Society, 1997) 778, at 780

22 Id at 779.

23 Chang asserts that “conflict must be effectively handled if it is not to be a barrier to progress” and that “conflict is best handled by managing it and adopting appropriate strategies to bring about a desired end". V Chang, How Can Conflict within a Group be Managed?, in K Martin, N Stanley & N Davison eds Teaching in the Disciplines/ Learning in Context, Proceedings of the 8th Annual Teaching Learning Forum, (Perth: UWA, 1999) 59-66. Joughin & Gardiner observe that “Facilitating independent learning involves increasing students’ responsibility for and control of their own learning...’Independent learning’ refers to learning which seeks to substantially increase student control of learning and which is substantially independent of the presence of a teacher. The teacher sets the parameters for learning and provides required resources while the student, or groups of students, controls the time, place and pace of their learning.” G Joughin & D Gardiner, A Framework for Teaching and Learning Law (Sydney: Centre for Legal Education, 1996) 60. However, they observe also that “Staff training in small group skills is often beneficial”. Id at 58.

24 At this early stage the authors were themselves to some extent unaware of the potential benefits and difficulties.

25 See in particular Case Study 1.

26 Miller, Trimbur & Wilkes note that “The personal and working relationships within the small groups can either make or break the course experience for many students.” J Miller J Trimbur & J Wilkes, Group Dynamics: Understanding Group Success and Failure in Collaborative Learning in K Bosworth & S Hamilton eds, Collaborative Learning: Underlying Processes and Effective Techniques (1994) 59 New Directions for Teaching and Learning 33, at 34.

27 Id, at 40.

28 McInnis, supra, note 5, at 2.

29 Used here as an anecdotal example and not as a case study.

30 Miller Trimbur & Wilkes identify variables including institutional or situational constraints such as timetabling, social calendar and physical space as being beyond a teacher’s control. Miller Trimbur & Wilkes, supra, note 26, at 40.

31 For example, the increasing student demands on academic and administrative staff which, if ignored, may affect students numbers or standards of excellence. Le Brun & Johnstone, supra, note 7, at 25.

32 Tang distinguishes between co-operative learning, initiated by teachers and collaborative learning, initiated by the students themselves. C Tang, Effects of Collaborative Learning on the Quality of Assignments, in B Dart and G Boulton-Lewis eds, Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research Ltd, 1998) 102.

33 “To maximise the effects of collaborative learning, teaching should provide support and create a context to facilitate group learning.” Tang, id at 120.