Hasche, Annette --- "Teaching Writing In Law: A Model to Improve Student Learning" [1992] LegEdRev 9; (1992) 3(2) Legal Education Review 267

TEACHING WRITING IN LAW: A MODEL TO IMPROVE STUDENT LEARNING

ANNETTE HASCHE *

[E]very year in almost every course, there are students whose work is assigned low grades because it lacks substance, clarity, creativity and sophistication. Why is such poor quality work produced?

This familiar problem was raised recently by Shirley Rawson and Alan Tyree. 1 The explanation focussed on by the authors is the failure of students to define or apply criteria for good work. The authors’ aim is accordingly to improve student performance by self and peer assessment which require the definition and application of criteria to evaluate one’s own or a peer student’s work.

My own aim in teaching has a slightly broader perspective. My primary concern is to improve students’ approach to learning and in particular to lead students to adopt a deep approach to learning.

Whereas a surface approach is characterised by rote learning and a focus on accurate reproduction of knowledge, 2 a deep approach to learning focuses on maximising understanding by reading widely, thinking critically, reflecting and linking new information to previous knowledge. 3 Students’ motivation would lie in learning for its own sake rather than purely in passing the course requirements.

If we look at Benjamin Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, 4 a deep approach to learning would clearly be of advantage in achieving the educational objectives of analysis, evaluation and synthesis, but also in terms of achieving the aims of comprehension, application and knowledge.

Making students aware of these approaches to learning and guiding them towards the adoption of a deep approach therefore seems to be an important aspect of teaching in higher education generally. Clearly, this should include legal education. We are not purely concerned with conveying knowledge about black letter law and teaching skills of application to the future profession. If we stopped there, the legal profession would be an agglomeration of petty technicians. We should aim at producing lawyers who know and can apply the law, but who are also able to critically evaluate it, detect socio-legal problems and make practical recommendations for their solution. 5 Accordingly, we must seek to develop analytical skills as well as critical and lateral thinking.

If we are seriously concerned to develop these skills and choose appropriate assessment tasks, 6 a deep approach to learning will mirror good performance in student work.

This article will canvass some of the current educational literature in two respects: teaching writing as an educational strategy and methods of teaching writing. A study undertaken by the author on teaching writing to a group of first year law students at the University of New South Wales Law School will be described. It will be demonstrated that teaching writing can lead to a deeper understanding of the subject matter being taught and can result in students changing their approach to learning towards a deep approach. My objective is to encourage law teachers to take an active role in teaching writing. Teachers will gain more personal satisfaction from teaching; students will gain a better approach to learning which will lead to a deeper level of understanding, analysis, critical thought and evaluation of the subject matter learned. Students’ work may no longer lack “substance, clarity, creativity and sophistication”.

WHY TEACH WRITING?

It is a fact that the written work of many students is of poor quality. Papers suffer from a lack of critical analysis, evaluation, lateral thinking and frequently also from poor presentation due to a lack of coherence and clarity. It is also a fact that most law teachers do not teach writing. Formal writing skills such as presentation, clarity, coherence are assumed to have been taught at secondary school or else students are referred to books on essay writing. 7 The link between writing and analysis, evaluation and synthesis skills is perhaps not perceived.

The question arises whether them could be a nexus between the lack of teaching writing and the poor quality work which students produce. Even on its own, the low grade papers seem to suggest a need for instruction in writing.

Unconscious of our own writing strategies, our advice to students will often be to write an outline before beginning to start writing, thereby depicting composing as a linear process. Research into the strategies of successful writers has revealed however, that writing is a non-linear process, 8 during which writers think a problem through, 9 discover meaning, ideas and revise their thinking. 10 Perhaps the most powerful writing strategy is to take a problem-solving approach to writing 11 which focuses on the three goals common to every writer: understanding of the issues to be discussed, effective communication of that understanding to the reader and persuading the reader to respond. 12 Implicit in this approach is thinking the problem through, generating ideas and revising them, organising ideas in a logical framework, analysing the reader, monitoring whether the paper achieves the writer’s goals and making the necessary changes. 13

The particular value I see in these strategies is, that, as Giggs 14 points out, this kind of reflective approach to writing parallels a deep approach to learning in general. 15 It is not surprising then to find that the existing research on writing indicates clearly that writing can promote learning. 16 If writing is a reflective process, it can lead to a deeper level of thinking about the subject matter, which can in turn deepen understanding and lead to critical analysis of the subject material, which can result in perceptive evaluation and synthesis. In addition, research conducted by Haynes 17 demonstrated a marked improvement in students’ work when they received guidance on the process of writing prior to receiving their assignment tasks.

Now you might accept everything I have said so far and yet dispute that it is you, the law teacher, who should familiarise the student with the concept of writing as a process. Let me explain why I think writing should be taught at law school, preferably in the first year, as recommended by Clanchy.18

It has been established that writing promotes learning in a variety of ways, in particular, subject understanding, critical analysis, evaluation and synthesis. If part of our educational objectives is the development of these skills, it follows that we should raise students’ awareness about writing as a process and give them plenty of opportunity to engage in the process of writing.

In addition, students must acquire the language of our discipline. As Clanchy 19 emphasises

The separation that is implied between content (science/ law/history) and the language in which that content is conveyed is not merely misleading, but unreal; New items of vocabulary need to be learned (both technical and non-technical jargon), new disciplinary styles or dialects acquired.

To paraphrase Clanchy: learning Law, learning to think like a lawyer, involves learning to read, to speak, to write legal English. 20

In sum, the literature suggests a correlation between writing and learning and between the use of language and subject content. There are indications that teaching writing improves student performance. These seem to be good reasons for teaching writing.

HOW TO TEACH WRITING?

In general, writing will have to be taught in context with a particular assignment task, for the students may otherwise not appreciate the benefit and/or the relevance of what we teach them about writing.

There are teaching methods which connect directly with a set task, whereas other techniques prepare students for writing tasks more generally. Let me focus on the latter first.

As has been argued, writing can enhance learning. Nightingale 21 recommends a number of activities which demand writing and serve as useful means to help students learn. Students can be encouraged or required to keep a course journal in which they note their thoughts and ideas about the reading and issues arising in class discussion. 22 Similar is Zubrick’s idea that students keep a reading log in which they record their reactions to the reading, in particular critical analysis, questions, links to something learned before. 23 Zubrick reduced her class contact hours to enable students to read widely in the subject area. She explains;

… reading logs were introduced … because of problems I had encountered in getting students to read, and to interact with what they read. However, I found that the logs had an equally important role in helping students to write, and to learn through writing (emphasis in the original). 24

Writing exercises can be integrated into the class in a useful way. As Nightingale 25 suggests, students can be asked at the beginning of a class to make a few written comments about the topic of the class. This is obviously practicable only when students are required to do preparatory reading. Another possibility is to ask students to explain in writing how a particular case relates to what had been at issue in the previous class. Discussion can be halted during the teaching session to give students the opportunity to write down their thoughts or questions about the topic so far. 26 At the end of the class students can be requested to record what in their view were the most important issues discussed and explain why they consider the ones listed important.

The principal reason to incorporate such writing exercises into teaching lies in their usefulness to encourage reflection and develop analytical and evaluative skills. Students will thereby both gain a deeper understanding of the subject matter and learn how to learn. An added benefit is that students may become more used to and comfortable with writing generally, which can help reduce student anxiety about formal writing tasks. 27 The use of these techniques should therefore not be regarded as a waste of valuable class time. 28

The methods of teaching I will consider now will be utilised in close connection with a formal assessment task.

As mentioned before, it will be helpful to students if they are made aware that writing is not a linear but a circular process, which requires reflection and revision at all stages. They may then engage in deeper thought about their set task than they might otherwise have done. 29 Likewise, their writing skills may improve if they approach writing as a problem- solving strategy and write with a clear perception of the needs of their readers in mind. 30 Such goal-directed writing will usually result in a more coherent paper which is well presented and clearly written.

Nightingale notes that teachers must choose assessment tasks which correspond with their aims in teaching. 31 The next step is to design a question which is clear, unambiguous and leaves no room for misinterpretation. 32 This requires some attempt to anticipate how students might interpret the question. 33

Furthermore, students should be told by which criteria you are going to assess their work. 34 In my experience, teachers tend to take it for granted that students know what is expected of them. This attitude is misguided, in my opinion, for two reasons.

Firstly, it appears likely that teachers do not always share the same expectations in relation to students’ work. As Nightingale 35 points out

many [tertiary teachers] discover that, in trying to grade without any specified criteria, they can identify particular traits in students’ work that they find attractive or distracting. I am aware, for instance, that what I call “fluency”, confident and cohesive expression, may seduce me to the extent that I fail to notice gaps in reasoning. Others concentrate on content to the extent that at first they do not notice sentence fragments. Others discover that they must struggle not to be put off by poor handwriting or any of dozens of other very important or almost inconsequential factors.

It seems vital therefore, that criteria for marking be established and discussed among colleagues who will share the responsibility for marking in a particular course. 36

Secondly, students will not always know what teachers expect of them. That seems to follow logically from the fact that teachers are not necessarily unanimous in the criteria they use for marking. Furthermore, Alan Braithwaite, Mark Trueman and James Hartley 37 conducted a study in which students were asked to list criteria which they believed were used in assessing their essays. The teachers who were responsible for marking those essays were also asked to indicate their criteria for marking. The researchers found that there was a discrepancy between students’ and teachers’ criteria:

|

Things tutors are believed to look for in assessing essays

|

Tutors’ criteria in assessing essays

|

|||

|

|

%

mentioning

(N = 82)

|

|

%

mentioning

(N = 7)

|

|

|

Originality

|

40

|

Evidence

|

57

|

|

|

Evidence

|

39

|

Reading

|

57

|

|

|

Structure/organization

|

35

|

Relevance

|

57

|

|

|

English

|

35

|

Structure/organization

|

57

|

|

|

Understanding

|

29

|

English

|

57

|

|

|

Argument

|

22

|

Effort

|

43

|

|

|

Relevance

|

17

|

Critical Interpretation

|

43

|

|

|

Reading

|

17

|

Argument

|

29

|

|

|

Appearance/presentation

|

12

|

Appearance/presentation

|

14

|

|

|

Critical interpretation

|

12

|

Understanding

|

14

|

|

|

Own opinions

|

11

|

|

|

|

Teachers should therefore tell students which criteria they are going to use in marking their work. Clanchy suggests that teachers should make their expectations concrete by making available to students a file of essays in various grades including marks and teachers’ comments for students to consult. 39 In this way, students can gain a tangible understanding of the requirements of a good paper. It may be even more worthwhile to explain to students why the good essays fulfil the criteria well and why the weaker papers do not. 40

The importance of open and constructive feedback is emphasised by Dai Hounsell. He is concerned that teacher feedback comes too late, namely after the paper is already written, to be of any use. 41 Clanchy reports that many departments in the Arts Faculty at ANU permit students to rewrite and resubmit their first essay. 42 In this way feedback can be used by the students to improve their work. It appears that only a small minority of students utilise this opportunity. 43 Another problem with feedback is, that comments are often purely negative in character (for instance “not enough analysis/evaluation”, “badly structured”) and not always understood by the students. If students are not taught academic discourse, they do not necessarily know what constitutes a good analysis or evaluation. 44 Clanchy advocates that feedback be “swift, detailed and individual” and recommends to conduct individual interviews with students. 45

Hounsell’s study shows also that students may fail to appreciate the general applicability of some teachers’ comments and consequently may regard the feedback given as irrelevant:

|

Interviewer:

|

Generally speaking, do you find tutor’s comments helpful?

|

|

Holly:

|

Not unless you get that title again, no.

|

|

Peter:

|

Sometimes I do read the comments but I find that I will never write the

same essay again anyway… 46

|

Hounsell concludes that it may be useful therefore to clearly differentiate content-related comments from those addressing notions of academic discourse. 47 Another option is to design a marking sheet which can rate students’ achievements on particular features of their work and which can be attached to their assignments. 48 If general aspects of academic discourse are used on those sheets, such as analysis, comprehension, evaluation, for instance, students may no longer limit the feedback provided to the confines of that particular paper.

PROJECT

In order to test the thesis that teaching writing can promote student learning, the author conducted a study with her students in 1991. The students were first year law students in the compulsory introductory course Legal System-Torts at the University of New South Wales Law School. Teaching in this subject is conducted by a group of four to five teachers in nine parallel groups of between twenty and forty students. The author was responsible for one group of twenty undergraduate students and one group of forty graduate students.

The first assessment task in 1991 was to write a case note, analysing the judgment(s) and putting the case in context with some issue which had already been discussed in class. Each student had to choose one case among three options.

METHOD

Very early in the course, the author gave students some hints on notetaking in and after class, using ideas by Hartley and Davies. 49 In addition, they were provided with a handout summarising those suggestions (see Appendix 1). The purpose of this was not purely to help students in taking useful notes, but primarily to emphasise the need for reflection, analysis, evaluation and synthesis early on and thereby encourage a deep approach to learning. It was recommended to students that they keep a course journal 50 in which they could include their notes, thoughts, questions, additional readings, relevant newspaper clippings etc.

Towards the beginning of the course the students also received a handout “Hints on: How to engage in active reading” (Appendix 2). With regard to academic articles included in the teaching materials, the aims were to lead students to reflective and purposeful reading and to make them conscious of academic writing. In relation to cases the objective was to give them a preliminary idea of the necessary elements of case analysis. Since the ability to analyse cases is one of the major skills students have to learn at law school, it seems natural to teach analytical skills. To this effect, the author worked very carefully through the cases to be discussed, examining the structure of judgments in detail as well as the language used by judges to emphasise the core of their judgments (such as “In my opinion …”, ‘The point is that …’l, ‘The comprehensive answer to the appellant’s arguments is …”).

Writing exercises integrated into the class such as described previously 51 were utilised in almost every class in order to develop students’ analytical and evaluative skills, encourage reflection and make students comfortable with writing in law. Occasionally students were asked to share what they had written with the class to demonstrate the range of valuable ideas. One particular writing task was to jot down a few points one would include in a case note on Mason’s judgment in SGIC v Trigwell 52 Some students shared their ideas with the class and the author pointed out which ideas were formally necessary to be included in a case note, which ones showed good evaluation and why and which comments demonstrated synthesis. The exercise was done in order to give students some concrete ideas on writing a case note.

In order to challenge the findings of Alan Braithwaite et al that “initial feedback during the first term seems to have little effect on [students] actions” 53 and to respond to the concerns that feedback may come too late to be regarded as useful by students, 54 the author gave students the option to write a case note on R v Wedge 55 in preparation for the assignment. They were instructed to direct their case note to a first year law student who missed the first few classes this year. This was done in order to get students to write for a different audience for, as Nightingale explains

[s]implifying complex ideas and explaining to someone with less knowledge is one way of demonstrating that one has really learned … Moreover, students who feel threatened by having to write for an experienced learned authority are also less anxious about writing for a non-authoritative (though hypothetical) reader. 56

They were given one week to write their papers and were told that their written answers would be read and commented upon by a fellow student first, and subsequently by the author. Almost all students used the opportunity of writing the case note before being handed out their formal assessment task. In the group of forty students, eight students did not write the voluntary exercise, in the group of twenty students four students did not do so.

Students were given a fellow student’s paper to read and comment upon and were asked to think about possible criteria for marking. In the following class, small groups were formed to discuss such criteria. 57 Subsequently students made suggestions for criteria which were written on the board. The author then provided them with a handout on Criteria for Assessment (Appendix 3), 58 which interestingly corresponded largely to the ones suggested by the students and discussed the order of importance. It was explained that the last four items on the list would not be formally assessed but would usually have some impact on the quality of their papers. The voluntary exercises were then read by the author and students were provided with written individual feedback within one week. 59 In addition to comments on the case note as such, students were given an indication as to what their answer revealed about their approach to learning. 60 When the papers were returned to the students, the different approaches to learning were explained to students, in particular, the advantages of adopting a deep approach to learning were emphasised. Two very good papers including the author’s comments to the writers of those case notes were made available to students to read. 61

After students had received their formal assessment task, the author spent fifteen minutes of one class to explain the process of writing to students. 62 In addition, students were given a handout, “Strategies for successful writing” (Appendix 4), which summarises the most important ideas.

With the feedback on the formal assessment task, students received a marking sheet which directly matched the list of criteria which students had received previously (Appendix 5). 63In addition, the students received an indication about their approach to learning again, as it became manifest in their papers.

OUTCOME

The outcome of the project was examined in various ways. A more informal impression was gained by assessing the atmosphere in class generally and by receiving individual feedback from some students. More reliable evidence was sought by asking all students to fill out a questionnaire on the effectiveness of teaching writing (Appendix 6). In addition, some measure of progress could be made on the basis of the formal case notes students had written.

Although it is difficult to document actual change in student behaviour, I have the impression that teaching writing has indeed enhanced learning for a significant proportion of students. Focussing on the students’ opinions first, the students clearly thought that the activities were generally very useful. I received some individual comments about the usefulness of the voluntary writing exercise in particular and the writing exercises integrated into the teaching. A few students praised my qualities as a teacher. The atmosphere in class became noticeably friendly during the project.

The answers given on the questionnaire were extremely positive. The students were most enthusiastic about the voluntary case note exercise and the individual feedback given on those papers. There was no negative or cautious comment in relation to these two activities apart from one or two complaints that the poorer quality papers received more feedback than the better ones. The class discussion and handout on criteria for marking was regarded as the third most effective activity with forty-three students describing this as either excellent, very good or important, or helpful and only two students expressing a view that the criteria were too obvious to require teacher guidance. Interesting to me was the positive feedback given on my suggestions on note-taking (forty-one students), something which most teachers would probably regard as spoon-feeding and unnecessary. Thirty-seven students liked the writing exercises in class, some commenting that these forced them to think and that they enjoyed this kind of active learning. Thirty-four students appreciated my comments and the handout on strategies for successful writing whilst eleven graduate students thought this was of limited or no benefit.

To my surprise, the feedback on the availability of two good papers on the voluntary exercise including my comments in the library was rather cautious, with only twenty seven students expressing a high opinion of this. Some students commented, however, that despite my repeated announcements of this they had not known that the papers were available or that they had been unable to get access to them.

The students were not convinced of the value of reading each others’ papers. Only three saw this as very good or excellent, whilst twenty-six students regarded it as good or helpful and fourteen as useless or of limited benefit.

For my own purposes, the answers given to questions nine and ten were most important. Students felt rather more hesitant about these questions than about the others. This is not surprising though, considering that these two were the only questions requesting an assessment of their own activities rather than of mine. Whilst eight students thought their writing had not changed as a result of the activities and seven thought so of their learning style, a few people said it was too early for a change or they were not sure. Twelve students noted that their writing style had changed, observing that their writing was now more focussed and concise. Ten students perceived a change in their learning style. Some made more specific comments, for instance, that they read in more depth now and engaged in more analysis and evaluation. A few students remarked that my teaching activities had conveyed what was expected of them and as a result they felt more self confident.

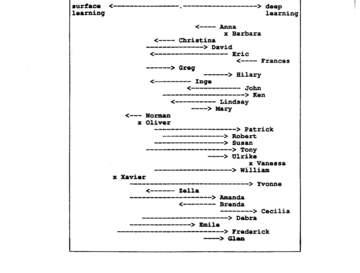

Although the students were rather cautious in their assessments of their approach to learning, their formal assignments evidenced some move towards a deep approach to learning. This can be illustrated in the following graphs which indicate my assessment of the students’ change in terms of depth of analysis, evaluation and synthesis from the voluntary paper to the formal case note. 64

GRAPH A

GROUP OF UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS 65

GRAPH B

GROUP OF GRADUATE STUDENTS

In this group the move was not as evident as in the group of undergraduate students, but there were still eighteen people who moved towards a deep approach as opposed to ten who moved the other way, while four students did not change. The explanation for a more mixed result in this group may lie in the fact that these students are graduate students. Consequently, their approach to learning would be fairly established. The difficulty of the case noted may therefore have had more impact on the depth of their papers than their way of learning did. The case used for the case note was much easier to analyse than the cases used for the formal assignment.

Although my assessment of a student’s approach to learning as more surface or more deep may be subjective to some extent and may have varied unconsciously from the exercise paper to the formal case note, the findings still seem fairly suggestive to me. Generally, a deep approach was reflected in a higher quality paper, although there were a few students who misinterpreted their case completely or who emphasised a discussion of the context of the case to such an extent that the analysis of the case itself suffered. Of the seven students who failed the assignment, three had not written the voluntary exercise and two rarely came to class and have therefore missed a lot of the Teaching Writing activities. 66 This seems fairly significant in itself, although it must be acknowledged that these students’ failure may have been due to some external cause such as a personal crisis or a general lack of interest.

SOME ISSUES

Further Action

It should be noted that the project was conducted during the first seven weeks of the year. To expect a change in students’ approach to learning within such a short period of time is indeed optimistic, particularly when account is taken of the fad that students have only just arrived in a learning environment which is likely to be very different from that where they have been before. It is important therefore, to continue to teach in a way which will encourage reflection, deep understanding, analysis and evaluation. To this effect writing exercises integrated into the class will be useful. Questioning should be used in a conscious way. Questions beginning with “why” will encourage reflection and comprehension. Queries such as “How does the reasoning process of these two judges differ?” will develop analytical skills. Something like “What are the five most important points you learned today?” will stimulate synthesis whereas “What do you think about this decision?” is directed at evaluation.

Improvements

The feedback given by the students suggests that the methods employed for teaching writing could be improved at least in two respects.

• Making good papers available to students to consult was generally perceived as a good idea, some students commented, however that they had not understood why these papers were good. Accordingly it seems that one should consider to follow Griffin’s suggestion 67to take the time to explain to students why the good papers were good. Alternatively, students could be asked to work this out in small groups and a short discussion in class could follow. • As reported before, most students did not think that reading each others’ exercise papers was particularly helpful. Some commented that the paper they had read was a very bad one (so they could not learn anything from it other than perhaps gain more confidence in their own capabilities), others felt hypocritical, criticising a peer student for something they might not feel able to do better themselves. Rawson and Tyree 68 report that in their experience, the students will usually respond adversely to peer assessment, primarily because “teacher knows best”. 69

This might have been the feeling of some of my students even though they were only asked to read and make comments, not mark. If the students felt this way, they did not say so however. To me the most likely reason seems that they did not know what was expected, since it was their first piece of writing in law. Some students commented indeed that they had felt lost. If this is true, two things follow.

If students are asked to read each others’ papers and make comments they should be told what to look for when reading, for instance, to examine the clarity and structure of the paper, as is proposed by Griffin. 70 But at a more fundamental level, this proves that students must be told what our expectations of them are. If they feel lost when reading another student’s paper, they must feel equally lost when writing their own paper. I see it as our responsibility as teachers to prevent these feelings arising and to tell students what our expectations are and by which criteria we are going to mark their papers. As mentioned previously a positive outcome of Teaching Writing for some of my students was that they felt more self-confident as a result of knowing what was expected of them.

Time Constraints

Reading your students’ voluntary exercises and providing them with individual feedback is such a time-consuming task that you would not consider doing it you may think. Students can get the opportunity to write a voluntary exercise paper without you having to go to so much trouble however. If the expectations are clearly explained to students before they write their paper and if peer reading is used in a more effective way by giving clear instructions to students what to look for when reading, the activity will still be very useful for students particularly those in their first year. In 1990 the author’s first year students were given a mock examination as a voluntary exercise to write at home. Again they were asked to read another student’s answer but were provided with a model answer. This works well with a problem type question, but would be fairly difficult to design for an essay type question or even a case note which requires evaluation and synthesis. After the students had read each others’ papers, the author skim-read all their papers in order to work out the general mistakes made. The students were then presented with a handout describing those general mistakes and explaining what to do instead. This was not very time consuming at all and still much appreciated by the students. As a result the examination papers were of a higher quality than the mock papers.

CONCLUSION

This study has demonstrated that teaching writing in law will improve student learning. Writing exercises integrated into the class have proved effective in encouraging reflection and developing analytical and evaluation skills. Individual feedback given to a voluntary assignment has resulted in significantly improved formal assignments. The study has also shown that students will adapt their approach to learning to their teacher’s expectations if those expectations are made explicit and concrete. Law teachers whose educational objectives include the development of skills in analysis, evaluation and synthesis will find that teaching writing in law is a very effective way of achieving their aims.

APPENDIX 1 - LEGAL SYSTEM/TORTS

Suggestions on Note Taking

Research findings show that students’ performance benefits from students taking notes in class and reviewing those notes for maximum retention. (J Hartley and I K Davies, “Note Taking: A Critical Review”, (1978) 15 PLET 207). The authors suggest the following activities for students (at 221):

• Note keywords or concepts in a diagrammatic format. • Record ideas that have personal meaning and give personal insights into the material. • Rewrite abbreviated/unstructured notes taken in class into a separate notebook. • Leave space at the beginning of any such notebook for contents/index pages. • Leave space for making additions to the notes. • Use some system for denoting points of importance (eg colour coding). • Give full references to notes made from any supplementary reading. (You never know when you may want to refer to that reading again.) • Review your notes. • With a set of notes taken from, say a lecture series or from several textbooks, try to create a master framework so as to integrate the notes into a meaningful whole. Add synthesis and evaluation to the analysis. • Try to consider your own notes as something meaningful to you.(Emphasis added)

When taking notes in class, make a point of noting your thoughts and queries as they come to mind. Do not just note every word the teacher said. Listen to cues given by your teacher as to whether something should be noted/is important or whether you should just listen and think.

When you review your notes and rewrite them to make a meaningful whole, use headings for issues/topics discussed and then list the relevant cases, secondary sources. and do not forget to include your own thoughts and reasoning.

For instance: The Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Laws.

- Relevant cases

- Murrell case 1836, Full Court of the Supreme Court of NSW

- Bonjon case 1841

... - Jungami 1981

...

Parties …

Material facts … Issue(s) …

Decision … (any dissent?)

Reasoning …

- Australian Law Reform Commission, The Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Laws 1986 p 57 Materials. Explain what is the thrust of the ALRC’s recommendations and their reasoning.

- Hookey, p 49 Materials. Arguments put forward by him.

- Any other material you have read.

- Your own thoughts, evaluation, conclusion.

APPENDIX 2 - HINTS ON: HOW TO ENGAGE IN ACTIVE READING

Articles

- Look at the title: what does it suggest to you?

- Look at the name of the author and her/his country of origin: do these bits of information raise any expectations of what might be in the text?

- Look at the headings: what do they suggest to you?

- Read the introduction and the conclusion first. Look for keywords, eg: “This paper will demonstrate …” “This chapter has shown how…”

- Skim body of text first: look for key passages and mark keywords such as “In my opinion …”. Look for words which are emphasised (eg italics). Often you will find central statements immediately before and after headings.

- Read text as a whole in detail. These techniques will enable you to: Increase your effectiveness and efficiency when reading. Engage in purposeful reading. Identify main ideas in a text. Become conscious of conventions of academic writing.

Cases

- Which court has decided the case and what is its position in the judicial hierarchy?

- When was the case decided? Was it first instance or appellate?

- Who were the parties?

- What were the material facts?

- What was the issue/were the issues the court had to consider?

- What was the court’s decision?

- Look for the key passages in the court’s reasoning.

APPENDIX 3 - LEGAL SYSTEM – TORTS - CRITERIA

FOR ASSESSMENT

CASE NOTE ASSIGNMENT

- Ability to analyse.

- Inclusion of all relevant matters.

- Comprehension.

- Evaluation and interpretation.

- Synthesis (how does this connect with what you already know about this area of the law?).

- Organisation and structure.

- Expression: conciseness, fluency.

- Acknowledgement of sources, footnoting.

- Grammar/syntax, punctuation, spelling.

APPENDIX 4 - STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESSFUL WRITING

Writing is a reflective process

Reflection

• What is the purpose of this exercise? • What do I really want to say? • Does the existing text so far say that? • Would a reader who does not know what I know, understand this? • What are my reader’s prior knowledge, attitudes and needs? • How well do I fulfil the criteria for assessment? (see separate handout)

Process

• Writing, reviewing and revising is a continual process towards the final product. • Make a plan to do and a plan to say, but be prepared to revise your plan • Generate and organise your ideas • Review your paper and consider whether it corresponds to your goals • Edit for conciseness. Write clear, direct sentences which say exactly what you mean • Edit for coherence (inner logic)

Getting started

• Brainstorm (list all ideas, do not censor initially) • Build a tree diagram (will show where some more thinking is required) • Use notation techniques (write down fragments, alternative phrasings as they come to mind, leaving generous margins for making changes)

When getting stuck

• Set sub-goals • Review and revise • Leave pick-up points

Keep the reader in mind

• Analyse your audience • Anticipate your reader’s response • Develop a reader-based structure

APPENDIX 5 - CASE NOTE ASSIGNMENT LEGAL SYSTEM — TORTS STUDENT’S NAME _____________________

|

|

Very Good;

|

Excellent

|

V. Good

|

Satis.

|

Poor

|

|

1

|

Ability to analyse

|

|

|

|

|

|

2

|

Inclusion of all

relevant matters

|

|

|

|

|

|

3

|

Comprehension

|

|

|

|

|

|

4

|

Evaluation and

interpretation

|

|

|

|

|

|

5

|

Synthesis (context)

|

|

|

|

|

|

6

|

Organisation and

structure

|

|

|

|

|

|

7

|

Expression:

conciseness, fluency

|

|

|

|

|

|

8

|

Acknowledgment

of sources

|

|

|

|

|

|

9

|

Footnoting

|

|

|

|

|

|

10

|

Grammar/syntax,

punctuation, spelling

|

|

|

|

|

General Comments:

___________________________________________________________________________________________

APPENDIX 6

STUDENT QUESTIONNAIRE

The purpose of this questionnaire is to provide me with your views on the effectiveness of some specific teaching activities I have engaged in since the beginning of this year. Please commenton the usefulness of the following activities/handouts.

- Handout – Suggestions on Note Taking

- Writing exercises in class (eg what would you include in a case note on Mason’s judgment in SGIC v Trigwell?)

- Voluntary case note exercise on R v Wedge

- Reading a fellow studen’t paper on Wedge.

- Class discussion and handout on criteria for marking.

- Individual feedback given on papers

- Availability of two good papers on R v Wedge in the library

- Handout – Strategies for successful writing

- Do you feel your writing has changed as a consequence of these activities? If so, how?

- Do you feel your learning style has changed as a result of these activities? If so, how?

[*] University of New South Wales Law School. I am grateful to Peggy Nightingale for helpful comments and suggestions.

© 1992. (1992) 3 Legal Educ Rev 267.

[1] S Rawson & AL Tyree, Self and Peer Assessment in Legal Education [1989] LegEdRev 11; (1989) 1 Legal Educ Rev 135.

[2] F Marton, D Hounsell and N Entwistle, The Experience of Learning, (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1984) at 159.

[3] Id.

[4] BS Bloom (ed), Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: Cognitive Domain, (New York: David McKay, 1956).

[5] It is not the place here to engage in a debate about the aims of legal education. Two valuable sources which discuss the wider objectives of legal education propagated here are D Pearce, E Campbell & D Harding, Australian Law Schools: A Discipline Assessment for the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission (Pearce Report), (Canberra: AGPS, 1987) and C Sampford & D Wood, Theoretical Dimensions of Legal Education — A Response to the Pearce Report (1988) 62 Aust LJ 32.

[6] The precise implications for choosing assessment tasks cannot be fully discussed here. Briefly, teachers should be aware that topics beginning with Analyse, Examine Critically, Evaluate, may encourage a deep approach, whereas topics beginning with Define, Summarise, List, Outline, may encourage a surface approach. See P Nightingale Improving Student Writing, Green Guide No 4, (Sydney: HERDSA 1986) at 4–6; J B Biggs, Surface and Deep Approaches to Writing Essays in Educational Research: Then and Now, (Hobart: Australian Association for Research in Education, 1985) 43, at 46. See also Sampford & Wood, supra note 5, at 36.

[7] J Clanchy & B Ballard; Essay Writing for Students, (Melbourne: Longman Cheshire, 1981) and L Flower, Problem-solving Strategies for Writing, 3rd ed (Orlando, Florida: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989), are very valuable books in this regard.

[8] This research is summarised by P Nightingale, Understanding Processes and Problems in Student Writing (1988) 13 Studies in Higher Educ 263 at 267–8.

[9] Flower, supra note 7, at 30; P Elbow, Teaching Thinking by Teaching Writing (1983) 15 Change 37.

[10] J Emig, Writing as a mode of learning (1977) 28 College Composition and Communication 122; L Odell, Teaching Writing by Teaching the Process of Discovery: An Interdisciplinary Enterprise, in LW Gregg and ER Steinberg Cognitive Processes in Writing, (New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1980) 139, at 143; Nightingale, supra note 8, at 270.

[11] Flower, supra note 7.

[12] Id at 5.

[13] Id.

[14] JB Biggs, Approaches to Learning and to Essay Writing in RR Schmeck ed Learning Strategies and Learning Styles, (New York; Plenum Press, 1988) 185, at 191.

[15] See text accompanying supra note 3.

[16] See for example CW Griffin, A Process to Critical Thinking: Using Writing to Teach Many Disciplines (1983) 31 Improving College and University Teaching 121 at 122; M Hewitson, Teaching Writing to Tertiary Students (1985) 7 HERDSA News 5, at 7; P Nightingale, supra note 6, at 1; FC Saul, Learning through Writing Skills, (1984) Chemical and Engineering News (5 November) 3, at 3.

[17] E Haynes, Using research in preparing to teach writing, (1978) 67 English Journal 84.

[18] J Clanchy, Improving Student Writing (1985) 7 HERDSA News 3, at 3.

[19] Id.

[20] Id; see also Nightingale, supra note 8, at 266 and Saul, supra note 16.

[21] Nightingale, supra note 16, at 10–14.

[22] Id at 10–11.

[23] A Zubrick, Learning through Writing: the Use of Reading Logs (1985) 7 HERDSA News 11 at 12.

[24] Id at 11.

[25] Nightingale, supra note 6, at 14.

[26] Id.

[27] Id at 15 and Odell, supra note 10, at 151.

[28] Id Odell.

[29] See text supra accompanying notes 8–10,

[30] See text supra accompanying notes 11–13.

[31] Nightingale, supra note 6, at 22; see also text in note 6 supra.

[32] Clanchy, supra note 18, at 4.

[33] Nightingale, supra note 6, at 5.

[34] Nightingale, supra note 6, at 23; Clanchy, supra note 18, at 3; Odell, supra note 10, at 152; Rawson & Tyree, supra note 1.

[35] Supra note 6, at 21–22.

[36] Id at 22.

[37] A Braithwaite, M Trueman & J Hartley, Writing Essays: the actions and strategies of students in: J Hartley, The Psychology of Written Communication (London: Kogan Page, 1980 ), at 98.

[38] Id at 100.

[39] Clanchy, supra note 18, at 4.

[40] Griffin, supra note 16, at 123.

[41] D Hounsell, Writing, Learning and Teaching. The Quality of Feedback, Conference Paper presented at an international conference on “Cognitive Processes in Student Learning”, University of Lancaster, 18–21 July 1985, at 14; see also Griffin, supra note 16, at 126.

[42] Supra note 18 at 4.

[43] Id.

[44] Hounsell, supra note 41, at 13; Clanchy, supra note 18, at 4.

[45] Id Clanchy.

[46] Hounsell, supra note 41, at 12.

[47] Id at 14.

[48] Id and Nightingale, supra note 6, at 33 with examples at 34–36.

[49] J Hartley and IK Davies, Note-taking: A critical review (1978) 15 PLET 207.

[50] See text supra accompanying note 22.

[51] See text supra accompanying notes 25–27.

[52] (1) [1979] HCA 40; 142 CLR 617.

[53] Supra note 37, at 105.

[54] Id, Hounsell, supra note 41, at 14; Griffin, supra note 16, at 126.

[55] (19761 1 NSWLR 581.

[56] Supra note 6, at 16.

[57] The idea that students should think about criteria for assessing their work derives from Odell, supra note 10, at 153 and G Gibbs, Teaching Students to Learn, (Milton Keynes, Open University Press, 1981), as reported in Nightingale, supra note 6, at 26–27.

[58] The need for this was emphasised in the text supra accompanying notes 34–38.

[59] Swift feedback was recommended by Clanchy, supra note 18, at 4 and the Easter recess was used to facilitate this.

[60] See infra, graphs A and B following note 64.

[61] See Clanchy, supra note 18.

[62] See text supra accompanying footnotes 29–30.

[63] This was drawn on a suggestion made by Hounsell, supra note 41, at 14.

[64] The names of all students have been changed to preserve their anonymity.

[65] ----> arrows indicate a change towards a deeper approach to learning, ie, deeper analysis, evaluation and synthesis.

<--- arrows indicate a change towards a surface approach to learning, ie, a focus on a mere summary of the case, listing the judge’s arguments rather than engaging in analysis, evaluation, synthesis.

* indicates no changes.[66] Two students failed as a result of a complete misinterpretation of their case.

[67] Griffin, supra note 16, at 123.

[68] Supra note l, at 136.

[69] Id at 141.

[70] Supra note 16, at 127–128.